Surgical paper III

Surgical management study of hepatic injury

Abstract

The incidences of the hepatorrhexis in trauma have markedly increased lately. In its treatment, there are still some difficulties due to acute massive hemorrhage. The clinical experiences are presented by the author. The Pringle technique, hepatorrhaphy, resectional debridement hepatotomy, hepatic artery selected libation and double catheter drainage have been employed. Postoperative treatment of re-hepatorrhagia, bile leakage or infection is emphatically recommended in emergency cases.

Key Words:

1. Traumatic Hepatorrnexis

2. Resectional Debridement Hepatotomy

3. Double catheter Drinage

May 11, 1990

As technological advancements in production and transportation continue to rise, so too does the incidence of hepatic trauma. These injuries often present as life-threatening conditions with a general mortality rate ranging from 20% to 25%. In a study conducted by McEarrall in 1962, 55% of 200 accidental deaths that occurred while walking were attributed to liver injuries. While modern medicine has made strides in reducing mortality rates through improved rescue technologies and blood transfusion methods, the liver's inherent fragility and thin capsule continue to pose challenges. Complications such as bile leakage and infection can arise in addition to hemorrhaging. The liver's unique anatomy, particularly the complexity surrounding the second porta hepatis, further complicates emergency surgical interventions. Given that the liver is not a paired organ, only partial excision is possible, adding another layer of complexity to its treatment. Despite the high risks associated with hepatic injuries, there remains a lack of uniform treatment standards. This paper reviews 35 clinical cases encountered over the past three decades, alongside a comprehensive literature review, to discuss various aspects of this challenging issue.

Non-Surgical Management of Superficial Hepatic Injuries

Clinical Experience

In our clinical practice, we have encountered three cases of superficial hepatic injuries. Upon surgical exploration, the lacerations were found to be superficial, and active bleeding had ceased. Consequently, suturing was deemed unnecessary; instead, the abdominal cavity was either cleaned or drained. All patients exhibited a stable postoperative course and made full recoveries.

Literature Review and Case Study

Superficial liver injuries that neither affect circulatory dynamics nor present with peritonitis or other complications can often be managed conservatively. Such injuries frequently self-terminate bleeding during the surgical intervention. Minor amounts of hemoptysis and bile leakage in the abdominal cavity are typically reabsorbed spontaneously.

Oldham's study reported 53 pediatric liver trauma cases, with 49 being managed conservatively. One illustrative case involved an 8-year-old boy who fell from a height of one meter. He experienced localized pain in his right hypochondriac region and mild discomfort in the lower right abdomen. Despite these symptoms, he displayed no muscle guarding, maintained normal blood pressure, and had a hemoglobin level of 120 g/L. A diagnostic aspiration of 2 ml of yellow, non-coagulated fluid from his abdomen confirmed liver injury. Hospitalized for three days without significant changes, he was discharged and observed for one month without complications. While the exact grade of liver injury was not surgically confirmed, it was presumed to be mild, and the patient exhibited a natural recovery.

Complications and Lessons Learned from Surgical Repair of Hepatic Injuries

Clinical Experience

During liver repair, the common practice of using mattress sutures may offer temporary hemostasis and wound closure. However, this technique often leads to complications such as necrotic infection and secondary hemorrhage. These adverse outcomes are primarily due to inadequate drainage, wound bed inactivation, autolysis of liver tissue, and bile accumulation.

Case Study

A 13-year-old male fell off the back of a cow, sustaining a transverse rupture in the center of his right liver upon impact with a cliffside. The surgical intervention employed mattress sutures for hemostasis and closed the liver wound, neglecting to perform common bile duct decompression and drainage. Although the patient initially recovered well postoperatively and was discharged after 14 days, he later developed hemobilia, recurrent right upper abdominal colic, hypotension, and anemia. Multiple rounds of blood transfusion and anti-infection measures proved ineffective over a week of conservative treatment. Subsequent surgery involved ligation of the hepatic artery and common bile duct drainage, leading to full recovery. A 10-year follow-up showed favorable growth and no residual sequelae.

Lessons and Recommendations

The key takeaway from this case is the critical need for debridement hepatectomy during the initial operation. This procedure removes necrotic liver tissue, followed by individual vessel ligations. Open drainage techniques, such as double-cannula negative pressure drainage, should be utilized. Alternatively, pedicled omentum can be loosely packed and affixed to the wound, in conjunction with common bile duct decompression and drainage. Implementing these measures can prevent the complications described above. Stone's research corroborates this approach, demonstrating successful hemostasis in 37 cases through the use of pedicled omentum packing in liver injuries.

Management of Large Vessel Injuries in the Second Porta Hepatis Region

Clinical Considerations

For injuries involving large vessels in the second porta hepatis area, it is crucial to provide ample exposure for manual pressure or non-injurious vascular clamping to temporarily halt bleeding. In situ repair of ruptured vessels can also yield successful outcomes. However, the use of Schrock catheter shunts is not universally applicable.

Case Study

A 42-year-old male, employed as a car driver, sustained injuries to the right retrohepatic bare area and a laceration of the inferior vena cava due to a vehicle rollover. A right thoracoabdominal incision was made to mobilize the liver. During wound exploration, profuse bleeding was encountered and temporarily controlled through emergency hand compression. Upon clearing the surgical field, a 0.5 cm tear in the inferior vena cava was discovered. Hemostasis was achieved through vessel repair using Satinsky forceps and continuous everting sutures with fine threads. Subsequently, liver laceration debridement and suturing were performed, leading to a successful outcome.

Clinical Implications

In cases like this, flipping the liver to expose the wound for hemostasis could exacerbate the tearing of already damaged vessels, thereby intensifying bleeding. Rapid blood transfusion would be futile in such situations and could precipitate intraoperative mortality.

The Pringle Method for Controlling Hemorrhage in Liver Trauma

Technique and Rationale

Intermittent hepatic pedicle occlusion via the Pringle method serves as an effective emergency measure for controlling acute and massive liver hemorrhage. This technique provides a vital buffer period, allowing for a thorough assessment of the injury and corresponding treatment planning. The efficacy of the Pringle method lies in its ability to target the hepatic artery and portal vein—the primary sources of bleeding in liver parenchymal injuries—due to their high intraluminal pressures. Conversely, hepatic veins, which unilaterally drain blood from the liver, contribute less to reflux hemorrhage.

Safety Measures

To minimize hepatic injury, it is advisable to follow the guideline of permitting normothermic reperfusion every 15 minutes for a 3-minute duration. Adherence to this protocol has been shown to mitigate liver damage.

Clinical Experience

The authors have also successfully employed the Pringle method during calculous hepatectomies when local hand pressure was impractical. This technique substantially reduced intraoperative blood loss. Remarkably, in five cases, left lateral hepatectomies were completed without the need for blood transfusion [3].

Manual Techniques for Hemostasis in Liver Surgery

Practical Approaches

During surgeries involving the left outer lobe of the liver or its surrounding areas, manual pressure or hand kneading can effectively control intraoperative bleeding. Additionally, irregular resections can be safely and conveniently performed.

Abdominal Hematocrit and Transfusion as an Emergency Measure in Liver Rupture

Criteria and Rationale

In the absence of concomitant hollow organ injuries, abdominal hematocrit and transfusion can serve as a feasible and effective emergency measure for managing liver ruptures. This approach is particularly beneficial when immediate external blood sources are unavailable.

Multifaceted Concerns in Liver Injury Management

Beyond Hemorrhage

Liver injuries pose challenges that extend beyond bleeding issues. Given the liver's intricate bile duct system, bile overflow can exacerbate peritonitis through chemical irritation. Furthermore, the liver's portal venous system, which collects blood from the digestive tract, presents a heightened risk for anaerobic infections.

Importance of Intraoperative Measures

Intraoperative drainage and perioperative prophylaxis against anaerobic infections are critical components in minimizing intra-abdominal infections. Earlier, we underestimated and inadequately managed these aspects, leading to secondary infections—a lesson that has since guided our approach.

Discussion

Ease of Diagnosis in Typical Cases

Diagnosing liver injuries is generally straightforward. For closed injuries, the presence of trauma to the right hypochondriac region, or an associated fracture of the right lower rib, coupled with right upper abdominal pain and internal bleeding, usually confirms the diagnosis through positive abdominal puncture tests.

Challenges in Less Obvious Cases

However, diagnostic difficulties arise when intra-abdominal hematoma is less than 200 ml, as abdominal puncture tests often return negative results. Moreover, such low volumes of intra-abdominal bleeding do not typically affect hemodynamics, complicating the diagnosis further. In these instances, abdominal lavage or repeated peritoneal punctures can yield positive results, thereby proving decisive for diagnosis.

Diagnostic Tools and Their Limitations

While visceral angiography and isotope-based liver scans using Selenium-76 and Isotope-198 offer valuable insights, they are not universally applicable. Non-invasive ultrasound and dynamic CT observations are beneficial alternatives. However, the dynamic observation of the hemogram proves to be of the utmost importance in these cases.

(1) Management of Hemorrhagic Shock

In the event of hemorrhagic shock, immediate measures should be taken to establish effective venous access, preferably in the upper limb. Additionally, a central venous pressure catheter should be inserted to ensure accurate monitoring and rapid volume expansion of the effective circulating blood volume. Concurrently, blood supplies should be actively prepared.

If the shock state persists and hemoglobin levels continue to decline, intraperitoneal liver blood transfusion may be performed under stringent conditions. This approach is particularly crucial in cases of massive acute hemorrhage, with increasing numbers of successful interventions reported in recent literature [4, 5].

When surgical intervention becomes necessary, it should be executed promptly alongside blood transfusion and preparation. This strategy aims to maximize the rescue opportunities for patients experiencing hemorrhage at rates exceeding the speed of blood transfusion.

(2) Mortality Rates and Surgical Approaches

(2) Research by Jaejackdavis indicates a 29% mortality rate for liver injuries treated with surgical resection. This rate can surge to 50% when conventional hepatectomies are performed. Consequently, debridement hepatectomies are the preferred surgical approach for liver contusions and lacerations to minimize further trauma.

Best Practices for Liver Surgery

During hepatic suture cutting, it is crucial to ensure adequate blood supply and bile drainage for the preserved liver segments. Failing to do so increases the risk of complications such as necrotic infections and bile leakage. Therefore, the guiding principles for liver trauma surgery include comprehensive debridement, effective hemostasis, prevention of bile leakage, and unobstructed drainage.

(3) Hepatic Artery Ligation: A Risk-Benefit Analysis

In severe liver injuries that are not amenable to hepatectomy or complications involving intra-hepatic vascular and biliary fistulas, selective hepatic artery ligation can offer a reliable hemostatic solution. The rationale behind this is that the portal vein provides 75% of the liver's blood supply and 50% of its oxygen. After ligation of a high-pressure hepatic artery, blood flow from the portal vein is enhanced. Collateral circulation can be established within 10 hours, typically eliminating the risk of liver necrosis. According to the Walt system, this approach can be effective in up to 31% of cases [6].

Postoperative Considerations

Post-ligation, transient spikes in serum markers like lactate dehydrogenase, transaminase, cholelithiasis, and alkaline phosphatase have been observed, but these levels normalize within 7–14 days. However, careful postoperative management is essential, including blood volume and oxygen supplementation, infection prevention, and dietary restrictions to mitigate the liver’s metabolic load. This technique should be used cautiously in patients with liver cirrhosis and liver diseases.

Operational Guidelines

During the procedure, excessive dissection in the porta hepatis region should be avoided to facilitate collateral circulation. Also, the ligation should be as close to the lesion as possible for targeted efficacy, avoiding the ligation of the liver's intrinsic arteries which could compromise the entire liver's blood supply.

(4) The Role of Common Bile Duct Decompression and Drainage

Aside from treating superficial injuries, common bile duct decompression and drainage should be considered a standard adjunctive procedure for managing this condition. This method facilitates bile drainage, mitigates intrahepatic cholestasis and bile leakage, and aids in infection control.

Monitoring and Diagnostic Benefits

The procedure serves as an essential monitoring tool for assessing postoperative liver function recovery and hemobilia (biliary tract bleeding). During the operation, methylene blue can be introduced to inspect for potential leaks in the intrahepatic bile ducts. Postoperatively, this technique can also be employed for angiographic studies.

(5) Hepatic Blood Transfusion in the Context of Massive Blood Loss

The liver has a rich blood supply, making severe injuries prone to extensive bleeding. The complications arising from massive blood transfusions cannot be overlooked. For instance, when transfusion volumes reach up to 4000ml, coagulation mechanisms can be disrupted, leading to uncontrolled bleeding.

Clinical Relevance

To mitigate this, hepatic blood transfusion becomes critically important. Ye [5] reported successful rescue in a case involving the transfusion of 6000ml of hepatic blood.

Theoretical Foundation

The theoretical underpinning is that the liver processes 1500ml of blood per minute and less than 1ml of bile. About 91% of bile is made up of water and inorganic salts, and the rest are trace amounts of substances like cholesterol and cholic acid. Therefore, mixing this with hepatic blood for transfusion poses no harm.

Practical Applications

Animal studies have confirmed the non-toxic nature of bile. Both anaerobic and regular cultures of liver blood from the portal vein have shown negative results, confirming its safety for transfusion.

Implementation Guidelines

For implementation, an abdominal puncture can be performed preoperatively to draw blood. A sterile suction device is then used for filtering and transfusion. If fresh blood is collected instead of pooled blood, anticoagulant measures are necessary. Otherwise, anticoagulants can be omitted, simplifying the process.

(6) Prevention of Postoperative Complications

(6) Loose suturing of the liver trauma is beneficial for drainage. The procedure should ensure that all areas around the liver, particularly the porta hepatis, are adequately drained.

Practical Recommendations

-

Drainage Systems: The use of double sets of silicon tube negative pressure suction systems is preferred in the porta hepatis region. This is to prevent complications like infections and bile leakage.

-

Pharmacological Measures: Antibiotics should be administered to minimize the risk of postoperative infections.

-

Blood Volume: Replenishing blood volume is essential for stabilizing the patient’s condition.

-

Liver Protection: Additional measures should be taken to protect the liver post-surgery.

-

Oxygen Supply: Oxygen should be administered as part of the postoperative care to ensure optimal recovery.

(7) Treatment of Combined Injuries

(7) When dealing with patients who have sustained multiple injuries, prioritization is key. Special attention must be paid to cerebral and thoracic trauma, as these can be life-threatening.

Practical Recommendations

-

Prioritization: Determine the most urgent injuries that need immediate treatment. Usually, head injuries and thoracic injuries take precedence due to their potential severity.

-

Simultaneous Treatment: Whenever possible, manage cerebral and thoracic traumas concurrently to maximize the chances of a successful outcome.

-

Exploration Post-Laparotomy: After opening the abdominal cavity, careful exploration of other internal organs is crucial. This is to identify and treat any other possible injuries and to prevent any complications like leakage.

-

Holistic Approach: By addressing all injuries in a coordinated manner, the success rate of the treatment is likely to improve.

(8) Conservative Treatment of Liver Trauma

The data presented by old ham [1] from Mott Children's Hospital in the U.S. shows that a conservative approach to liver trauma can often be effective. Out of 188 cases of closed abdominal trauma, 53 involved liver injuries. Only four required emergency surgery due to acute hemorrhage. The rest were managed non-operatively, with only three later requiring delayed surgical intervention due to complications from biliary peritonitis. This results in a relatively low surgical intervention rate of 13.2% (7/53).

Key Points to Consider

-

CT and Liver Enzyme Monitoring: Any conservative treatment must involve rigorous monitoring, including CT scans and liver enzyme tests (GOT, GPT).

-

Hematocrit Levels: It's crucial to maintain hematocrit levels above 30% to ensure effective treatment.

-

Medical Support: Excellent medical services and the availability of surgical intervention at any time are necessary.

-

Risks: Such a conservative approach does carry risks, including post-transfusion hepatitis and the potential for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

-

Long-term Effects: The impact of abdominal blood on long-term adhesive intestinal obstruction remains inconclusive.

-

Clinical Judgement: Based on clinical experience, liver trauma that does not cause hemodynamic changes can be managed conservatively with thorough monitoring and responsible clinical observation.

References

[1] Oidham KT et al. "Blunt liver injure in childhood: Evolution of therapy and current perspective." J Current Surg. 1988;45(1):41

[2] Stone HH et al. "Use of pedicle omentum as an autogenous pack for control of hemorrhage in major injuries of the liver." S.G.O. 1975;141:92

[3] Li, Mingjie. "Left Lateral Hepatectomy for Intrahepatic Gallstones" 国内医学外科分册 1980; 161; 皖南医学 1980;13:51

[4] Lu, Xianding. "Report of 4 Cases of Intra-abdominal Hematocrit and Transfusion Due to Traumatic Liver Rupture" 中华外科杂志 1980; 18(3):211

[5] Ye, Shengdan. "A Case Report of Massive Liver Blood Transfusion for Traumatic Liver Rupture" 实用外科杂志 1986: 6(3):425

[6] Walt HJ. "Discussion of hepatic artery ligation." Surg 1979; 86:536

Contributors

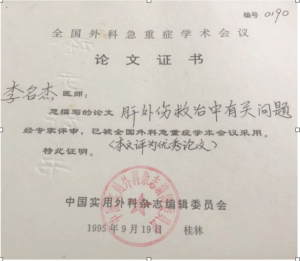

Wuhu Changhang Hospital

-

- Li, Mingjie

- Wang, Yueqin

This article was originally published in "交通医学 (Transportation Medicine)" 1996; 10(1): 60-62. (A paper presented at the Transportation Ministry's 1990 Surgical Academic Symposium).

from 李名杰 王月琴:肝外伤救治中的几个问题