2.0. Introduction

This chapter examines the role of grammar in handling the three major types of morpho-syntactic interface problems. This investigation justifies the mono-stratal design of CPSG95 which contains feature structures of both morphology and syntax.

The major observation from this study is: (i) grammatical analysis, including both morphology and syntax, plays the fundamental role in contributing to the solutions of the morpho-syntactic problems; (ii) when grammar alone is not sufficient to reach the final solution, knowledge beyond morphology and syntax may come into play and serve as “filters” based on the grammatical analysis results.[1] Based on this observation, a study in the direction of interleaving morphology and syntax will be pursued in the grammatical analysis. Knowledge beyond morphology and syntax is left to future research.

Section 2.1 investigates the relationship between grammatical analysis and the resolution of segmentation ambiguity. Section 2.2 studies the role of syntax in handling Chinese productive word formation. The borderline cases and their relationship with grammar are explored in 2.3. Section 2.4 examines the relevance of knowledge beyond syntax to segmentation disambiguation. Finally, a summary of the presented arguments and discoveries is given in 2.5.

2.1. Segmentation Ambiguity and Syntax

Segmentation ambiguity is one major problem which challenges the traditional word segmenter or an independent morphology. The following study shows that this ambiguity is structural in nature, not fundamentally different from other structural ambiguity in grammar. It will be demonstrated that sentential structural analysis is the key to this problem.

A huge amount of research effort in the last decade has been made on resolving segmentation ambiguity (e.g. Chen and Liu 1992; Gan 1995; He, Xu and Sun 1991; Liang 1987; Lua 1994; Sproat, Shih, Gale and Chang 1996; Sun and T’sou 1995; Sun and Huang 1996; X. Wang 1989; Wu and Su 1993; Yao, Zhang and Wu 1990; Yeh and Lee 1991; Zhang, Chen and Chen 1991; Guo 1997b). Many (e.g. Sun and Huang 1996; Guo 1997b) agree that this is still an unsolved problem. The major difficulty with most approaches reported in the literature lies in the lack of support from sufficient grammar knowledge. To ultimately solve this problem, grammatical analysis is vital, a point to be elaborated in the subsequent sections.

2.1.1. Resolution of Hidden Ambiguity

The topic of this section is the treatment of hidden ambiguity. The conclusion out of the investigation below is that the structural analysis of the entire input string provides a sound basis for handling this problem.

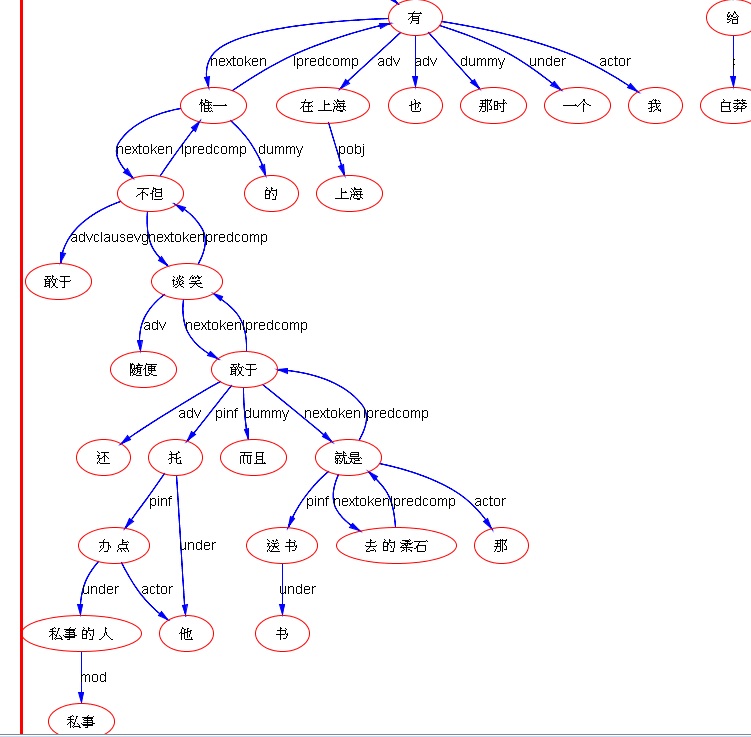

The following sample sentences illustrate a typical case involving the hidden ambiguity string 烤白薯 kao bai shu.

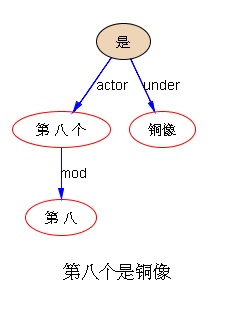

(2-1.) (a) 他吃烤白薯

ta | chi | kao-bai-shu

he | eat | baked-sweet-potato

[S [NP ta] [VP [V chi] [NP kao-bai-shu]]]

He eats the baked sweet potato.

(b) * ta | chi | kao | bai-shu

he | eat | bake | sweet-potato

(2-2.) (a) * 他会烤白薯

ta | hui | kao-bai-shu.

he | can | baked-sweet-potato

(b) ta | hui | kao | bai-shu.

he | can | bake | sweet-potato

[S [NP ta] [VP [V hui] [VP [V kao] [NP bai-shu]]]]

He can bake sweet potatoes.

Sentences (2-1) and (2-2) are a minimal pair; the only difference is the choice of the predicate verb, namely chi (eat) versus hui (can, be capable of). But they have very different structures and assume different word identification. This is because verbs like chi expect an NP object but verbs like hui require a VP complement. The two segmentations of the string kao bai shu provide two possibilities, one as an NP kao-bai-shu and the other as a VP kao | bai-shu. When the provided unit matches the expectation, it leads to a successful syntactic analysis, as illustrated by the parse trees in (2‑1a) and (2-2b). When the expectation constraint is not satisfied, as in (2-1b) and (2-2a), the analysis fails. These examples show that all candidate words in the input string should be considered for grammatical analysis. The disambiguation choice can be made via the analysis, as seen in the examples above with the sample parse trees. Correct segmentation results in at least one successful parse.

He, Xu and Sun (1991) indicate that a hidden ambiguity string requires a larger context for disambiguation. But they did not define what the 'larger context' should be. The following discussion attempts to answer this question.

The input string to the parser constitutes a basic context as well as the object for sentential analysis.[2] It will be argued that this input string is the proper context for handling the hidden ambiguity problem. The point to be made is, context smaller than the input string is not reliable for the hidden ambiguity resolution. This point is illustrated by the following examples of the hidden ambiguity string ge ren in (2-3).[3] In each successive case, the context is expanded to form a new input string. As a result, the analysis and the associated interpretation of ‘person’ versus ‘individual’ change accordingly.

(2-3.) input string reading(s)

(a) 人 ren person (or man, human)

[N ren]

(b) 个人 ge ren individual

[N ge-ren]

(c) 三个人 san ge ren three persons

[NP [CLAP [NUM san] [CLA ge]] [N ren]]

(d) 人的力量 ren de li liang the human power

[NP [DEP [NP ren] [DE de]] [N li-liang]]

(e) 个人的力量 ge ren de li liang the power of an individual

[NP [DEP [NP ge-ren] [DE de]] [N li-liang]]

(f) 三个人的力量 san ge ren de li liang the power of three persons

[NP [DEP [NP [CLAP [NUM san] [CLA ge]] [N ren]] [DE de]] [N li-liang]]

(g) 他不是个人 ta bu shi ge ren.

(1) He is not a man. (He is a pig.)

[S [NP ta] [VP [ADV bu] [VP [V shi] [NP [CLAP ge] [N ren]]]]]

(2) He is not an individual. (He represents a social organization.)

[S [NP ta] [VP [ADV bu] [VP [V shi] [NP ge-ren]]]]

Comparing (a), (b) with (c), and (d), (e) with (f), one can see the associated change of readings when each successively expanded input string leads to a different grammatical analysis. Accordingly, one segmentation is chosen over the other on the condition that the grammatical analysis of the full string can be established based on the segmentation. In (b), the ambiguous string is all that is input to the parser, therefore the local context becomes full context. It then acquires the lexical reading individual as the other possible segmentation ge | ren does not form a legitimate combination. This reading may be retained, as in (e), or changed to the other reading person, as in (c) and (f), or reduced to one of the possible interpretations, as in (g), when the input string is further lengthened. All these changes depend on the sentential analysis of the entire input string, as shown by the associated structural trees above. It demonstrates that the full context is required for the adequate treatment of the hidden ambiguity phenomena. Full context here refers to the entire input string to the parser.

It is necessary to explain some of the analyses as shown in the sample parses above. In Contemporary Mandarin, a numeral cannot combine with a noun without a classifier in between.[4] Therefore, the segmentation san (three) | ge-ren (individual) is excluded in (c) and (f), and the correct segmentation san (three) | ge (CLA) | ren (person) leads to the NP analysis. In general, a classifier alone cannot combine with the following noun either, hence the interpretation of ge ren as one word ge-ren (individual) in (b) and (e). A classifier usually combines with a preceding numeral or determiner before it can combine with the noun. But things are more complicated. In fact, the Chinese numeral yi (one) can be omitted when the NP is in object position. In other words, the classifier alone can combine with a noun in a very restricted syntactic environment. That explains the two readings in (g).[5]

The following is a summary of the arguments presented above. These arguments have been shown to account for the hidden ambiguity phenomena. The next section will further demonstrate the validity of these arguments for overlapping ambiguity as well.

(2-4.) Conclusion

The grammatical analysis of the entire input string is required for the adequate treatment of the hidden ambiguity problem in word identification.

2.1.2. Resolution of Overlapping Ambiguity

This section investigates overlapping ambiguity and its resolution. A previous influential theory is examined, which claims that the overlapping ambiguity string can be locally disambiguated. However, this theory is found to be unable to account for a significant amount of data. The conclusion is that both overlapping ambiguity and hidden ambiguity require a context of the entire input string and a grammar for disambiguation.

For overlapping ambiguity, comparing different critical tokenizations will be able to detect it, but such a technique cannot guarantee a correct choice without introducing other knowledge. Guo (1997) pointed out:

As all critical tokenizations hold the property of minimal elements on the word string cover relationship, the existence of critical ambiguity in tokenization implies that the “most powerful and commonly used” (Chen and Liu 1992, page 104) principle of maximum tokenization would not be effective in resolving critical ambiguity in tokenization and implies that other means such as statistical inferencing or grammatical reasoning have to be introduced.

However, He, Xu and Sun (1991) claim that overlapping ambiguity can be resolved within the local context of the ambiguous string. They classify the overlapping ambiguity string into nine types. The classification is based on the categories of the assumably correctly segmented words in the ambiguous strings, described below.

Suppose there is an overlapping ambiguous string consisting of ABC; both AB and BC are entries listed in the lexicon. There are two possible cases. In case one, the category of A and the category of BC define the classification of the ambiguous string. This is the case when the segmentation A|BC is considered correct. For example, in the ambiguous string 白天鹅 bai tian e, the word AB is bai-tian (day-time) and the word BC is tian-e (swan). The correct segmentation for this string is assumed to be A|BC, i.e. bai (A: white) | tian-e (N: swan) (in fact, this cannot be taken for granted as shall be shown shortly), therefore, it belongs to the A-N type. In case two, i.e. when the segmentation AB|C is considered correct, the category of AB and the category C define the classification of the ambiguous string. For example, in the ambiguous string 需求和 xu qiu he, the word AB is xu-qiu (requirement) and the word BC qiu-he (sue for peace). The correct segmentation for this string is AB|C, i.e. xu-qiu (N: requirement) | he (CONJ: and) (again, this should not be taken for granted), therefore, it belongs to the N-CONJ type.

After classifying the overlapping ambiguous strings into one of nine types, using the two different cases described above, they claim to have discovered a rule.[6] That is, the category of the correctly segmented word BC in case one (or AB in case two) is predictable from AB (or BC in case two) within the local ambiguous string. For example, the category of tian-e (swan) in bai | tian-e (white swan) is a noun. This information is predictable from bai tian within the respective local string bai tian e. The idea is, if ever an overlapping ambiguity string is formed of bai tian and C, the judgment of bai | tian-C as the correct segmentation entails that the word tian-C must be a noun. Otherwise, the segmentation A|BC is wrong and the other segmentation AB|C is right. For illustration, it is noted that tian-shi (angel) in the ambiguous string 白天使 bai | tian-shi (white angel) is, as expected, a noun. This predictability of the category information from within the local overlapping ambiguous string is seen as an important discovery (Feng 1996). Based on this assumed feature of the overlapping ambiguous strings, He, Xu and Sun (1991) developed their theory that an overlapping ambiguity string can be disambiguated within the local string itself.

The proposed disambiguation process within the overlapping ambiguous string proceeds as follows. In order to correctly segment an overlapping ambiguous string, say, bai tian e or bai tian shi, the following information needs to be given under the entry bai-tian (day-time) in the tokenization lexicon: (i) an ambiguity label, to indicate the necessity to call a disambiguation rule; (ii) the ambiguity type A-N, to indicate that it should call the rule corresponding to this type. Then the following disambiguation rule can be formulated.

(2-5.) A-N type rule (He, Xu and Sun 1991)

In the overlapping ambiguous string A(1)...A(i) B(1)...B(j) C(1)...C(k),

if B(1)...B(j) and C(1)...C(k) form a noun,

then the correct segmentation is A(1)...A(i) | B(1)...B(j)-C(1)...C(k),

else the correct segmentation is A(1)...A(i)-B(1)...B(j) | C(1)...C(k).

This way, bai tian e and bai tian shi will always be segmented as bai (white) | tian-e (swan) and bai (white) | tian-shi (angel) instead of bai-tian (daytime) | e (goose) and bai-tian (daytime) | shi (make). This can be easily accommodated in a segmentation algorithm provided the above information is added to the lexicon and the disambiguation rules are implemented. The whole procedure is running within the local context of the overlapping ambiguous string and uses only lexical information. So they also name the overlapping ambiguity disambiguation morphology-based disambiguation, with no need to consult syntax, semantics or discourse.

Feng (1996) emphasizes that He, Xu and Sun's view on the overlapping ambiguous string constitutes a valuable contribution to the theory of Chinese word identification. Indeed, this overlapping ambiguous string theory, if it were right, would be a breakthrough in this field. It in effect suggests that the majority of the segmentation ambiguity is resolvable without and before a grammar module. A handful of simple rules, like the A-N type rule formulated above, plus a lexicon would solve most ambiguity problems in word identification.[7]

Feng (1996) provides examples for all the nine types of overlapping ambiguous strings as evidence to support He, Xu and Sun (1991)'s theory. In the case of the A-N type ambiguous string bai tian e, the correct segmentation is supposed to be bai | tian-e in this theory. However, even with his own cited example, Feng ignores a perfect second reading (parse) when the time NP bai-tian (daytime) directly acts as a modifier for the sentence with no need for a preposition, as shown in (2‑6b) below.

(2-6.) 白天鹅游过来了

bai tian e you guo lai le (Feng 1996)

(a) bai | tian-e | you | guo-lai | le.

white | swan | swim | over-here | LE

[S [NP bai tian-e] [VP you guo-lai le]]

The white swan swam over here.

(b) bai-tian | e | you | guo-lai | le.

day-time | goose | swim | over-here | LE

[S [NP+mod bai-tian] [S [NP e] [VP you guo-lai le]]]

In the day time the geese swam over here.

In addition, one only needs to add a preposition zai (in) to the beginning of the sentence to make the abandoned segmentation bai-tian | e the only right one in the changed context. The presumably correct segmentation, namely bai | tian-e, now turns out to be wrong, as shown in (2-7a) below.

(2-7.) 在白天鹅游过来了

zai bai tian e you guo lai le

(a) * zai | bai | tian-e | you | guo-lai | le.

in | white | swan | swim | over-here | LE

(b) zai | bai-tian | e | you | guo-lai | le.

in | day-time | goose | swim | over-here | LE

[S [PP+mod zai bai-tian] [S [NP e] [VP you guo-lai le]]]

In the day time the geese swam over here.

The above counter-example is by no means accidental. In fact, for each cited ambiguous string in the examples given by Feng, there exist counter-examples. It is not difficult to construct a different context where the preferred segmentation within the local string, i.e. the segmentation chosen according to one of the rules, is proven to be wrong.[8] In the pairs of sample sentences (2‑8) through (2-10), (a) is an example which Feng (1996) cited to support the view that the local ambiguous string itself is enough for disambiguation. Sentences in (b) are counter-examples to this theory. It is a notable fact that the listed local string is often properly contained in a more complicated ambiguous string in an expanded context, seen in (2-9b) and (2-10b). Therefore, even when the abandoned segmentation can never be linguistically correct in any context, as shown for tu-xing (graph) | shi (BM) in (2-9) where a bound morpheme still exists after the segmentation, it does not entail the correctness of the other segmentation in all contexts. These data show that all possible segmentations should be retained for the grammatical analysis to judge.

(2-8.) V-N type of overlapping ambiguous string

研究生命

yan jiu sheng ming:

yan-jiu (V:study) | sheng-ming (N:life)

yang-jiu-sheng (N:graduate student) | ming (life/destiny)

(a) 研究生命的本质

yan-jiu sheng-ming de ben-zhi

study life DE essence

Study the essence of life.

(b) 研究生命金贵

yan-jiu-sheng ming jin-gui

graduate-student life precious

Life for graduate students is precious.

(2-9.) CONJ-N type of overlapping ambiguous string

和平等 he ping deng:

he (CONJ:and) | ping-deng (N:equality)

he-ping (N:peace) | deng (V:wait)?

(a) 独立自主和平等互利的原则

du-li-zi-zhu he ping-deng-hu-li de yuan-ze

independence and equal-reciprocal-benefit DE principle

the principle of independence and equal reciprocal benefit

(b) 和平等于胜利 he-ping deng-yu sheng-li

peace equal victory

Peace is equal to victory.

(2-10.) V-P type of overlapping ambiguous string

看中和 kan zhong he:

kan-zhong (V:target) | he (P:with)

kan (V:see) | zhong-he (V:neutralize)

(a) 他们看中和日本人生意的机会

ta-men kan-zhong he ri-ben ren zuo sheng-yi de ji-hui

they target with Japan person do business DE opportunity

They have targeted the opportunity to do business with the Japanese.

(b) 这要看中和作用的效果

zhe yao kan zhong-he-zuo-yong de xiao-guo

this need see neutralization DE effect

This will depend on the effects of the neutralization.

The data in (b) above directly contradict the claim that an overlapping ambiguous string can be disambiguated within the local string itself. While this approach is shown to be inappropriate in practice, the following comment attempts to reveal its theoretical motivation.

As reviewed in the previous text, He, Xu and Sun (1991)'s overlapping ambiguity theory is established on the classification of the overlapping ambiguous strings. A careful examination of their proposed nine types of the overlapping ambiguous strings reveals an underlying assumption on which the classification is based. That is, the correctly segmented words within the overlapping ambiguous string will automatically remain correct in a sentence containing the local string. This is in general untrue, as shown by the counter-examples above.[9] The following analysis reveals why.

Within the local context of the overlapping ambiguous string, the chosen segmentation often leads to a syntactically legitimate structure while the abandoned segmentation does not. For example, bai (white) | tian-e (swan) combines into a valid syntactic unit while there is no structure which can span bai-tian (daytime) | e (goose). For another example, yan-jiu (study) | sheng-ming (life) can be combined into a legitimate verb phrase [VP [V yan-jiu] [NP sheng-ming]], but yan-jiu-sheng (graduate student) | ming (life/destiny) cannot. But that legitimacy only stands locally within the boundary of the ambiguous string. It does not necessarily hold true in a larger context containing the string. As shown previously in (2-7a), the locally legitimate structure bai | tian-e (white swan) does not lead to a successful parse for the sentence. In contrast, the locally abandoned segmentation bai-tian (daytime) | e (goose) has turned out to be right with the parse in (2-7b). Therefore, the full context instead of the local context of the ambiguous string is required for the final judgment on which segmentation can be safely abandoned. Context smaller than the entire input string is not reliable for the overlapping ambiguity resolution. Note that exactly the same conclusion has been reached for the hidden ambiguous strings in the previous section.

The following data in (2-11) further illustrate the point of the full context requirement for the overlapping ambiguity resolution, similar to what has been presented for the hidden ambiguity phenomena in (2-3). In each successive case, the context is expanded to form a new input string. As a result, the interpretation of ‘goose’ versus ‘swan’ changes accordingly.

(2-11.) input string reading(s)

(a) 鹅 e goose

[N e]

(b) 天鹅 tian e swan

[N tian-e]

(c) 白天鹅 bai tian e white swan

[N [A bai] [N tian-e]]

(d) 鹅游过来了 e you guo lai le.

The geese swam over here.

[S [NP e] [VP you guo-lai le]]

(e) 天鹅游过来了 tian e you guo lai le.

The swans swam over here.

[S [NP tian-e] [VP you guo-lai le]]

(f) 白天鹅游过来了 bai tian e you guo lai le.

(i) The white swan swam over here.

[S [NP bai tian-e] [VP you guo-lai le]]

(ii) In the daytime, the geese swam over here.

S [NP+mod bai-tian] [S [NP e] [VP you guo-lai le]]]

(g) 在白天鹅游过来了 zai bai tian e you guo lai le.

In the daytime, the geese swam over here.

[S [PP zai bai-tian] [S [NP e] [VP you guo-lai le]]]

(h) 三只白天鹅游过来了 san zhi bai tian e you guo lai le.

Three white swans swam over here.

[S [NP san zhi bai tian-e] [VP you guo-lai le]]

It is interesting to compare (c) with (f), (g) and (h) to see their associated change of readings based on different ways of segmentation. In (c), the overlapping ambiguous string is all that is input to the parser, therefore the local context becomes full context. It then acquires the reading white swan corresponding to the segmentation bai | tian-e. This reading may be retained, or changed, or reduced to one of the possible interpretations when the input string is lengthened. That is respectively the case in (h), (g) and (f). All these changes depend on the grammatical analysis of the entire input string. It shows that the full context and a grammar are required for the resolution of most ambiguities; and when sentential analysis cannot disambiguate - in cases of ‘genuine’ segmentation ambiguity like (f), the structural analysis can make explicit the ambiguity in the form of multiple parses (readings).

In the light of the inquiry in this section, the theoretical significance of the distinction between overlapping ambiguity and hidden ambiguity seems to have diminished.[10] They are both structural in nature. They both require full context and a grammar for proper treatment.

(2-12.) Conclusion

(i) It is not necessarily true that an overlapping ambiguous string can be disambiguated within the local string.

(ii) The grammatical analysis of the entire input string is required for the adequate treatment of the overlapping ambiguity problem as well as the hidden ambiguity problem.

2.2. Productive Word Formation and Syntax

This section examines the connection of productive word formation and segmentation ambiguity. The observation is that there is always a possible involvement of ambiguity with each type of word formation. The point to be made is that no independent morphology systems can resolve this ambiguity when syntax is unavailable. This is because words formed via morphology, just like words looked up from lexicon, only provide syntactic ‘candidate’ constituents for the sentential analysis. The choice is decided by the structural analysis of the entire sentence.

Derivation is a major type of productive word formation in Chinese. Section 1.2.2 has given an example of the involvement of hidden ambiguity in derivation, repeated below.

(2-13.) 这道菜没有吃头 zhe dao cai mei you chi tou.

(a) zhe | dao | cai | mei-you | chi-tou

this | CLA | dish | not-have | worth-of-eating

[S [NP zhe dao cai] [VP [V mei-you] [NP chi-tou]]]

This dish is not worth eating.

(b) ? zhe | dao | cai | mei-you | chi | tou

this | CLA | dish | not have | eat | head

[S [NP zhe dao cai] [VP [ADV mei-you] [VP [V chi] [NP tou]]]]

This dish did not eat the head.

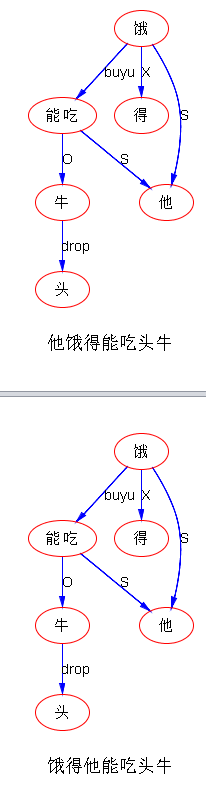

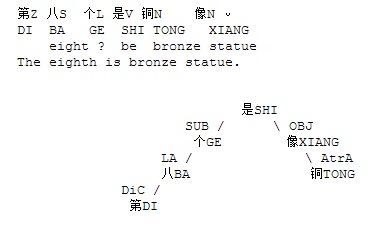

(2-14.) 他饿得能吃头牛 ta e de neng chi tou niu.

(a) * ta | e | de | neng | chi-tou | niu

he | hungry | DE3 | can | worth-of-eating | ox

(b) ta | e | de | neng | chi | tou | niu

he | hungry | DE3 | can | eat | CLA | ox

[…[VP [V e] [DE3P [DE3 de] [VP [V neng] [VP [V chi] [NP tou niu]]]]]]

He is so hungry that he can eat an ox.

Some derivation rule like the one in (2-15) is responsible for combining the transitive verb stem and the suffix –tou (worth-of) into a derived noun for (2-13a) and (2-14a).

(2-15.) X (transitive verb) + tou --> X-tou (noun, semantics: worth-of-X)

However, when syntax is not available, there is always a danger of wrongly applying this morphological rule due to possible ambiguity involved, as shown in (2-14a). In other words, morphological rules only provide candidate words; they cannot make the decision whether these words are legitimate in the context.

Reduplication is another method for productive word formation in Chinese. An outstanding problem is the AB --> AABB reduplication or AB --> AAB reduplication if AB is a listed word. In these cases, some reduplication rules or procedures need to be involved to recognize AABB or AAB. If reduplication is a simple process confined to a local small context, it may be possible to handle it by incorporating some procedure-based function calls during the lexical lookup. For example, when a three-character string, say 分分心 fen fen xin, cannot be found in the lexicon, the reduplication function will check whether the first two characters are the same, and if yes, delete one of them and consult the lexicon again. This method is expected to handle the AAB type reduplication, e.g. fen-xin (divide-heart: distract) --> fen-fen-xin (distract a bit).

But, segmentation ambiguity can be involved in reduplication as well. Compare the following examples in (2-16) and (2-17) containing the sub-string fen fen xin, the first is ambiguity free but the second is ambiguous. In fact, (2‑17) involves an overlapping ambiguous string shi fen fen xin: shi (ten) | fen-fen-xin (distract a bit) and shi-fen (very) | fen-xin (distract). Based on the conclusion presented in 2.1, it requires grammatical analysis to resolve the segmentation ambiguity. This is illustrated in (2‑17).

(2-16.) 让他分分心

rang | ta | fen-fen-xin

let | he | distracted-a-bit

Let him relax a while.

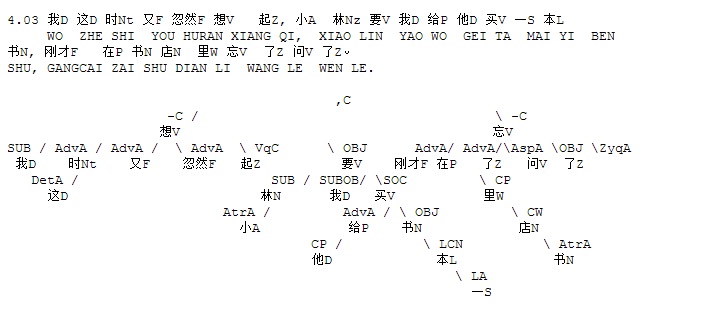

(2-17.) 这件事十分分心

zhe jian shi shi fen fen xin.

(a) * zhe | jian | shi | shi | fen-fen-xin

this | CLA | thing | ten | distracted a bit

(b) zhe | jian | shi | shi-fen | fen-xin

this | CLA | thing | very | distract

[S [NP zhe jian shi] [VP [ADV shi-fen] [V fen-xin]]]

This thing is very distracting.

Finally, there is also possible ambiguity involvement in the proper name formation. Proper names for persons, locations, etc. that are not listed in the lexicon are recognized as another major problem in word identification (Sun and Huang 1996).[11] This problem is complicated when ambiguity is involved.

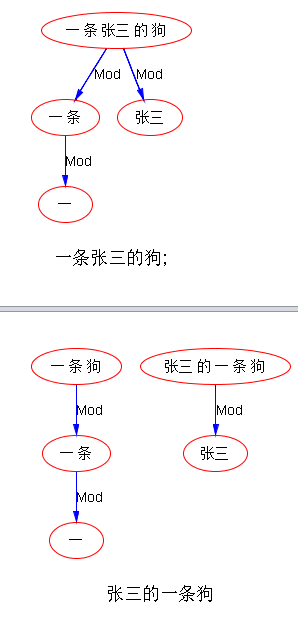

For example, a Chinese person name usually consists of a family name followed by a given name of one or two characters. For example, the late Chinese chairman mao-ze-dong (Mao Zedong) used to have another name li-de-sheng (Li Desheng). In the lexicon, li is a listed family name. Both de-sheng and sheng mean ‘win’. This may lead to three ways of word segmentation, a complicated case involving both overlapping ambiguity and hidden ambiguity: (i) li | de-sheng; (ii) li-de | sheng; (iii) li-de-sheng, as shown in (2-18) below.

(2-18.) 李得胜了 li de sheng le.

(a) li | de-sheng | le

Li | win | LE

[S [NP li] [VP de-sheng le]]

Li won.

(b) li-de | sheng | le

Li De | win | LE

[S [NP li de] [VP sheng le]]

Li De won.

(c) * li-de-sheng | le

Li Desheng | LE

For this particular type of compounding, the family name serves as the left boundary of a potential compound name of person and the length can be used to determine candidates.[12] Again, the choice is decided by the grammatical analysis of the entire sentence, as illustrated in (2-18).

(2-19.) Conclusion

Due to the possible ambiguity involvement in productive word formation, a grammar containing both morphology and syntax is required for an adequate treatment. An independent morphology system or separate word segmenter cannot solve ambiguity problems.

2.3. Borderline Cases and Grammar

This section reviews some outstanding morpho-syntactic borderline phenomena. The points to be made are: (i) each proposed morphological or syntactic analysis should be justified in terms of capturing the linguistic generality; (ii) the design of a grammar should facilitate the access to the knowledge from both morphology and syntax in analysis.

The nature of the borderline phenomena calls for the coordination of morphology and syntax in a grammar. The phenomena of Chinese separable verbs are one typical example. The co-existence of their contiguous use and separate use leads to the confusion whether they belong to the lexicon and morphology, or whether they are syntactic phenomena. In fact, as will be discussed in Chapter V, there are different degrees of ‘separability’ for different types of Chinese separable verbs; there is no uniform analysis which can handle all separable verbs properly. Different types of separable verbs may justify different approaches to the problems. In terms of capturing linguistic generality, a good analysis should account for the demonstrated variety of separated uses and link the separated use and the contiguous use.

‘Quasi-affixation’ is another outstanding interface problem. This problem requires careful morpho-syntactic coordination. As presented in Chapter I, structurally, ‘quasi-affixes’ and ‘true’ affixes demonstrate very similar word formation potential, but ‘quasi-affixes’ often retain some ‘solid’ meaning while the meaning of ‘true’ affixes are functionalized. Therefore, how to coordinate the semantic contribution of the derived words via ‘quasi-affixation’ in the context of the building of the semantics for the entire sentence is the key. This coordination requires flexible information flow between data structures for morphology, syntax and semantics during the morpho-syntactic analysis.

In short, the proper treatment of the morpho-syntactic borderline phenomena requires inquiry into each individual problem in order to reach a morphological or syntactic analysis which maximally captures linguistic generality. It also calls for the design of a grammar where information between morphology and syntax can be effectively coordinated.

2.4. Knowledge beyond Syntax

This section examines the roles of knowledge beyond syntax in the resolution of segmentation ambiguity. Despite the fact that further information beyond syntax may be necessary for a thorough solution to segmentation ambiguity,[13] it will be argued that syntax is the appropriate place for initiating this process due to the structural nature of segmentation ambiguity.

Depending on which type of information is essential for the disambiguation, disambiguation can be classified as structure-oriented, semantics-oriented and pragmatics-oriented. This classification hierarchy is modified from that in He, Xu and Sun (1991). They have classified the hidden ambiguity disambiguation into three categories: syntax-based, semantics-based and pragmatics-based. Together with the morphology-based disambiguation which is equivalent to the overlapping ambiguity resolution in their theory, they have built a hierarchy from morphology up to pragmatics.

A note on the technical details is called for here. The term X‑oriented (where X is either syntax, semantics or pragmatics) is selected here instead of X-based in order to avoid the potential misunderstanding that X is the basis for the relevant disambiguation. It will be shown that while information from X is required for the ambiguity resolution, the basis is always syntax.

Based on the study in 2.1, it is believed that there is no morphology-based (or morphology-oriented) disambiguation independent of syntax. This is because the context of morphology is a local context, too small for resolving structural ambiguity. There is little doubt that the morphological analysis is a necessary part of word identification in terms of handling productive word formation. But this analysis cannot by itself resolve ambiguity, as argued in 2.2. The notion 'structure' in structure-oriented disambiguation includes both syntax and morphology.

He, Xu and Sun (1991) exclude the overlapping ambiguity resolution in the classification beyond morphology. This exclusion is found to be not appropriate. In fact, both the resolution of hidden ambiguity and overlapping ambiguity can be classified into this hierarchy. In order to illustrate this point, for each such class, I will give examples from both hidden ambiguity and overlapping ambiguity.

Sentences in (2-20) and (2-21) which contain the hidden ambiguity string 阵风zhen feng are examples for the structure-oriented disambiguation. This type of disambiguation relying on a grammar constitutes the bulk of the disambiguation task required for word identification.

(2-20.) 一阵风吹过来了

yi zhen feng chui guo lai le. (Feng 1996)

(a) yi | zhen | feng | chui | guo-lai | le

one | CLA | wind | blow | over-here | LE

[S [NP [CLAP yi zhen] [N feng]] [VP chui guo-lai le]]

A gust of wind blew here

(b) * yi | zhen-feng | chui | guo-lai | le

one | gusts-of-wind | blow | over-here | LE

(2-21.) 阵风会很快来临 zhen feng hui hen kuai lai lin.

(a) zhen-feng | hui | hen | kuai | lai-lin

gusts-of-wind | will | very | soon | come

[S [NP zhen-feng] [VP hui hen kuai lai-lin]]]

Gusts of wind will come very soon.

(b) * zhen | feng | hui | hen | kuai | lai-lin

CLA | wind | will | very | soon | come

Compare (2-20a) where the ambiguity string is identified as two words zhen (CLA) feng (wind) and (2-21a) where the string is taken as one word zhen-feng (gusts-of-wind). Chinese syntax defines that a numeral cannot directly combine with a noun, neither can a classifier alone when it is in non-object position. The numeral and the classifier must combine together before they can combine with a noun. So (2-20b) and (2‑21b) are both ruled out while (2-20a) and (2-21a) are structurally well-formed.

For the structure-oriented overlapping ambiguity resolution, numerous examples have been cited before, and one typical example is repeated below.

(2-22.) 研究生命金贵 yan jiu sheng ming jin gui

(a) yan-jiu-sheng | ming | jin-gui

graduate student | life | precious

[S [NP yan-jiu-sheng] [S [NP ming] [AP jin-gui]]]

Life for graduate students is precious.

(b) * yan-jiu | sheng-ming | jin-gui

study | life | precious

As a predicate, the adjective jin-gui (precious) syntactically expects an NP as its subject, which is saturated by the second NP ming (life) in (2-22a). The first NP serves as a topic of the sentence and is semantically linked to the subject ming (life) as its possessive entity.[14] But there is no parse for (2-22b) despite the fact that the sub-string yan-jiu sheng-ming (to study life) forms a verb phrase [VP [V yan-jiu] [NP sheng-ming]] and the sub-string sheng-ming jin-gui (life is precious) forms a sentence [S [NP sheng-ming] [AP jin-gui]]. On one hand, the VP in the subject position does not satisfy the syntactic constraint (the category NP) expected by the adjective jin-gui (precious) - although other adjectives, say zhong-yao 'important', may expect a VP subject. On the other hand, the transitive verb yan-jiu (study) expects an NP object. It cannot take an S object (embedded object clause) as do other verbs, say ren-wei (think).

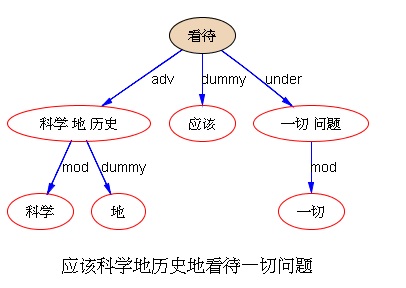

The resolution of the following hidden ambiguity belongs to the semantics-oriented disambiguation.

(2-23.) 请把手抬高一点儿 qing ba shou tai gao yi dian er (Feng 1996)

(a1) qing | ba | shou | tai | gao | yi-dian-er

please | BA | hand | hold | high| a-little

[VP [ADV qing] [VP ba shou tai gao yi-dian-er]]

Please raise your hand a little higher.

(a2) * qing | ba | shou | tai | gao | yi-dian-er

invite | BA | hand | hold | high | a-little

(b1) * qing | ba-shou | tai | gao | yi-dian-er

please | N:handle | hold | high | a-little

(b2) ? qing | ba-shou | tai | gao | yi-dian-er

invite | N:handle | hold | high | a-little

[VP [VG [V qing] [NP ba-shou]] [VP tai gao yi-dian-er]]

Invite the handle to hold a little higher.

This is an interesting example. The same character qing is both an adverb ‘please’ and a verb ‘invite’. (2-23b2) is syntactically valid, but violates the semantic constraint or semantic selection restriction. The logical object of qing (invite) should be human but ba-shou (handle) is not human. The two syntactically valid parses (2-23a1) and (2-23b2), which correspond to two ways of segmentation, are expected to be somehow disambiguated on the above semantic grounds.

The following case is an example of semantics-oriented resolution of the overlapping ambiguity.

(2-24.) 茶点心吃了 cha dian xin chi le.

(a1) cha | dian-xin | chi | le

tea | dim sum | eat | LE

[S [NP+object cha dian-xin] [VP chi le]]

The tea dim sum was eaten.

(a2) ? cha | dian-xin | chi | le

tea | dim sum | eat | LE

[S [NP+agent cha dian-xin] [VP chi le]]

The tea dim sum ate (something).

(a3) ? cha | dian-xin | chi | le

tea | dim sum | eat | LE

[S [NP+object cha ] [S [NP+agent dian-xin] [VP chi le]]]

Tea, the dim sum ate.

(a4) ? cha | dian-xin | chi | le

tea | dim sum | eat | LE

[S [NP+agent cha ] [VP [NP+object dian-xin] [VP chi le]]]

The tea ate the dim sum.

(b1) ? cha-dian | xin | chi | le

tea dim sum | heart | eat | LE

[S [NP+object cha-dian] [S [NP+agent xin] [VP chi le]]]

The tea dim sum, the heart ate.

(b2) ? cha-dian | xin | chi | le

tea dim sum | heart | eat | LE

[S [NP+agent cha-dian] [VP [NP+object xin] [VP chi le]]]

The tea dim sum ate the heart.

Most Chinese dictionaries contain the listed compound noun cha-dian (tea-dim-sum), but not cha dian-xin which stands for the same thing, namely the snacks served with the tea. As shown above, there are four analyses for one segmentation and two analyses for the other segmentation. These are all syntactically legitimate, corresponding to six different readings. But there is only one analysis which makes sense, namely the implicit passive construction with the compound noun cha dian-xin as the preceding (logical) object in (a1). All the other five analyses are nonsense and can be disambiguated if the semantic selection restriction that animate being eats (i.e. chi) food is enforced. Syntactically, (a2) is an active construction with the optional object omitted. The constructions for (a3) and (b1) are of long distance dependency where the object is topicalized and placed at the beginning. The SOV (Subject Object Verb) pattern for (a4) and (b2) is a very restrictive construction in Chinese.[15]

The pragmatics-oriented disambiguation is required for the case where ambiguity remains after the application of both structural and semantic constraints.[16] The sentences containing this type of ambiguity are genuinely ambiguous within the sentence boundary, as shown with the multiple parses in (2-25) for the hidden ambiguity and (2-26) for the overlapping ambiguity below.

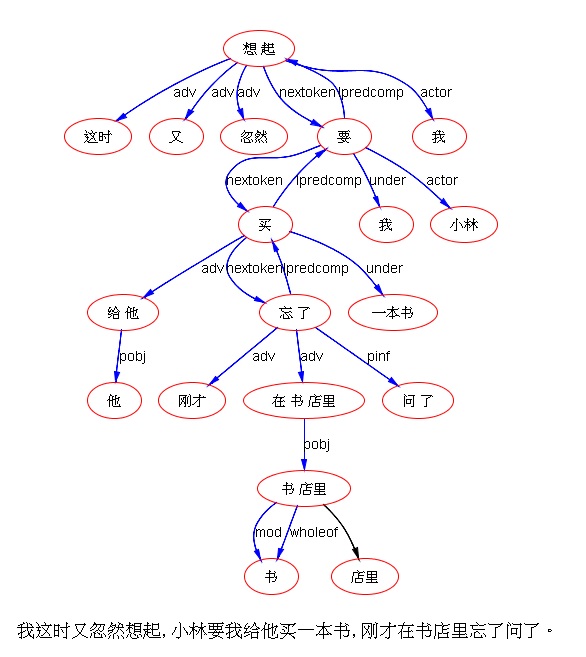

(2-25.) 他喜欢烤白薯 ta xi huan kao bai shu.

(a) ta | xi-huan | kao | bai-shu.

he | like | bake | sweet-potato

[S [NP ta] [VP [V xi-huan] [VP [V kao] [NP bai-shu]]]]

He likes baking sweet potatoes.

(b) ta | xi-huan | kao-bai-shu.

he | like | baked-sweet-potato

[S [NP ta] [VP [V xi-huan] [NP kao-bai-shu]]]

He likes the baked sweet potatoes.

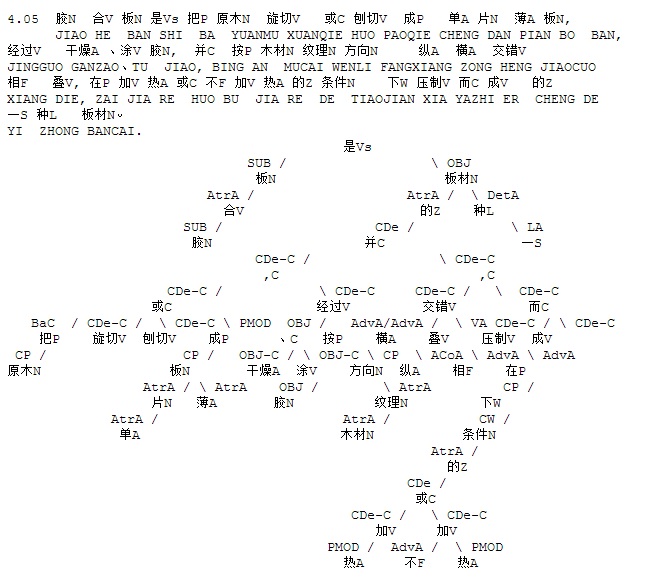

(2-26.) 研究生命不好 yan jiu sheng ming bu hao

(a) yan-jiu-sheng | ming | bu | hao.

graduate student | destiny | not | good

[S [NP yan-jiu-sheng] [S [NP ming] [AP bu hao]]]

The destiny of graduate students is not good.

(b) yan-jiu | sheng-ming | bu | hao.

study | life | not | good

[S [VP yan-jiu sheng-ming] [AP bu hao]]

It is not good to study life.

An important distinction should be made among these classes of disambiguation. Some ambiguity must be solved in order to get a reading during analysis. Other ambiguity can be retained in the form of multiple parses, corresponding to multiple readings. In either case, it demonstrates that at least a grammar (syntax and morphology) is required. The structure-oriented ambiguity belongs to the former, and can be handled by the appropriate structural analysis. The semantics-oriented ambiguity and the pragmatics-oriented ambiguity belong to the latter, so multiple parses are a way out. The examples for different classes of ambiguity show that the structural analysis is the foundation for handling ambiguity problems in word identification. It provides possible structures for the semantic constraints or pragmatic constraints to work on.

In fact, the resolution of segmentation ambiguity in Chinese word identification is but a special case of the resolution of structural ambiguity for NLP in general. As a matter of fact, the grammatical analysis has been routinely used to resolve, and/or prepare the basis for resolving, the structural ambiguity like the PP attachment.[17]

2.5. Summary

The most important discovery in the field of Chinese word identification presented in this chapter is that the resolution of both types of segmentation ambiguity involves the analysis of the entire input string. This means that the availability of a grammar is the key to the solution of this problem.

This chapter has also examined the ambiguity involvement in productive word formation and reached the following conclusion. A grammar for morphological analysis as well as for sentential analysis is required for an adequate treatment of this problem. This establishes the foundation for the general design of CPSG95 as consisting of morphology and syntax in one grammar formalism. [18]

The study of the morpho-syntactic borderline problems shows that the sophisticated design of a grammar is called for so that information between morphology and syntax can be effectively coordinated. This is the work to be presented in Chapter III and Chapter IV. It also demonstrates that each individual borderline problem should be studied carefully in order to reach a morphological or syntactic analysis which maximally captures linguistic generality. This study will be pursued in Chapter V and Chapter VI.

----------------------------------------------------------

[1] Constraints beyond morphology and syntax can be implemented as subsequent modules, or “filters”, in order to select the correct analysis when morpho-syntactic analysis leads to multiple results (parses). Alternatively, such constraints can also be integrated into CPSG95 as components parallel to, and interacting with, morphology and syntax. W. Li (1996) illustrates how semantic selection restriction can be integrated into syntactic constraints in CPSG95 to support Chinese parsing.

[2] In theory, if discourse is integrated in the underlying grammar, the input can be a unit larger than sentence, say, a paragraph or even a full text. But this will depend on the further development in discourse theory and its formalization. Most grammars in current use assume sentential analysis.

[3] Similar examples for the overlapping ambiguity string will be shown in 2.1.2.

[4] But in Ancient Chinese, a numeral can freely combine with countable nouns.

[5] These two readings in written Chinese correspond to an obvious difference in Spoken Chinese: ge (CLA) in (g1) is weakened in pronunciation, marked by the dropping of the tone, while in (g2) it reads with the original 4th tone emphatically.

[6] It is likely that what they have found corresponds to Guo’s discovery of “one tokenization per source” (Guo 1998). Guo’s finding is based on his experimental study involving domain (“source”) evidence and seems to account for the phenomena better. In addition, Guo’s strategy in his proposal is also more effective, reported to be one of the best strategies for disambiguation in word segmenters.

[7] According to He, Xu and Sun (1991)'s statistics on a corpus of 50833 Chinese characters, the overlapping ambiguous strings make up 84.10%, and the hidden ambiguous strings 15.90%, of all ambiguous strings.

[8] Guo (1997b) goes to the other extreme to hypothesize that “every tokenization is possible”. Although this seems to be a statement too strong, the investigation in this chapter shows that at least domain independently, local context is very unreliable for making tokenization decision one way or the other.

[9] However, this assumption may become statistically valid within a specific domain or source, as examined in Guo (1998). But Guo did not give an operational definition of source/domain. Without such a definition, it is difficult to decide where to collect the domain-specific information required for disambiguation based on the principle one tokenization per source, as proposed by Guo (1998).

[10] This distinction is crucial in the theories of Liang (1987) and He, Xu and Sun (1991).

[11] This work is now defined as one fundamental task, called Named Entity tagging, in the world of information extraction (MUC-7 1998). There has been great advance in developing Named Entity taggers both for Chinese (e.g. Yu et al 1997; Chen et al 1997) and for other languages.

[12] That is what was actually done with the CPSG95 implementation. More precisely, the family name expects a special sign with hanzi-length of 1 or 2 to form a full name candidate.

[13] A typical, sophisticated word segmenter making reference to knowledge beyond syntax is presented in Gan (1995).

[14] This is in fact one very common construction in Chinese in the form of NP1 NP2 Predicate. Other examples include ta (he) tou (head) tong (ache): ‘he has a head-ache’ and ta (he) shen-ti (body) hao (good): 'he is good in health'.

[15] For the detailed analysis of these constructions, see W. Li (1996).

[16] It seems that it may be more appropriate to use terms like global disambiguation or discourse-oriented disambiguation instead of the term pragmatics-oriented disambiguation for the relevant phenomena.

[17] It seems that some PP attachment problems can be resolved via grammatical analysis alone. For example, put something on the table; found the key to that door. Others require information beyond syntax (semantics, discourse, etc.) for a proper solution. For example, see somebody with telescope. In either case, the structural analysis provides a basis. The same thing happens to the disambiguation in Chinese word identification.

[18] In fact, once morphology is incorporated in the grammar, the identification of both vocabulary words and non-listable words becomes a by-product during the integrated morpho-syntactic analysis. Most ambiguity is resolved automatically and the remaining ambiguity will be embodied in the multiple syntactic trees as the results of the analysis. This has been shown to be true and viable by W. Li (1997, 2000) and Wu and Jiang (1998).

[Related]

PhD Thesis: Morpho-syntactic Interface in CPSG (cover page)

PhD Thesis: Chapter I Introduction

PhD Thesis: Chapter II Role of Grammar

PhD Thesis: Chapter III Design of CPSG95

PhD Thesis: Chapter IV Defining the Chinese Word

PhD Thesis: Chapter V Chinese Separable Verbs

PhD Thesis: Chapter VI Morpho-syntactic Interface Involving Derivation

PhD Thesis: Chapter VII Concluding Remarks

Overview of Natural Language Processing

Dr. Wei Li’s English Blog on NLP