Interaction of syntax and semantics in parsing Chinese transitive verb patterns *

(old paper in Proceedings of International Chinese Computing Conference, ICCC'96)

Wei LI

Department of Linguistics, Simon Fraser University

Burnaby, B.C. V5A 1S6 CANADA (email: [email protected])

Keywords: Chinese processing, transitive pattern, syntax, semantics, lexical rule, HPSG

Abstract

This paper addresses the problem of parsing Chinese transitive verb patterns (including the BA construction and the BEI construction) and handling the related phenomena of semantic deviation (i.e. the violation of the semantic constraint).

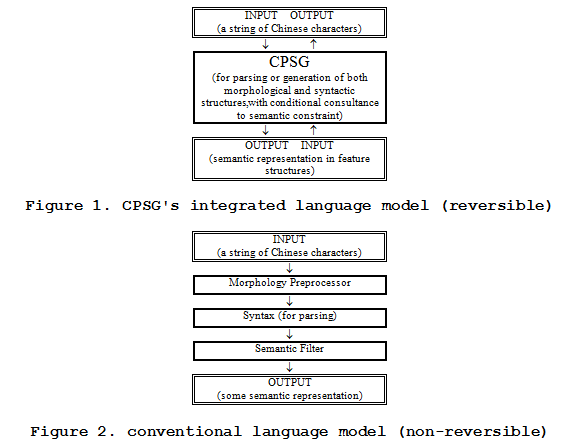

We designed a syntax-semantics combined model of Chinese grammar in the framework of Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar [Pollard & Sag 1994]. Lexical rules are formulated to handle both the transitive patterns which allow for semantic deviation and the patterns which disallow it. The lexical rules ensure the effective interaction between the syntactic constraint and the semantic constraint in analysis.

The contribution of our research can be summarized as:

(1) the insight on the interaction of syntax and semantics in analysis;

(2) a proposed lexical rule approach to semantic deviation based on (1);

(3) the application of (2) to the study of the Chinese transitive patterns;

(4) the implementation of (3) in an unification-based Chinese HPSG prototype.

- Background

When Chomsky proposed his Syntactic Structures in Fifties, he seemed to indicate that syntax should be addressed independently of semantics. As a convincing example, he presented a famous sentence:

1) Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

Weird as it sounds, the grammaticality of this sentence is intuitively acknowledged: (1) it follows the English syntax; (2) it can be interpreted. In fact, there is only one possible interpretation, solely decided by its syntactic structure. In other words, without the semantic interference, our linguistic knowledge about the English syntax is sufficient to assign roles to each constituent to produce a reading although the reading does not seem to make sense.

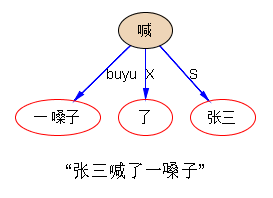

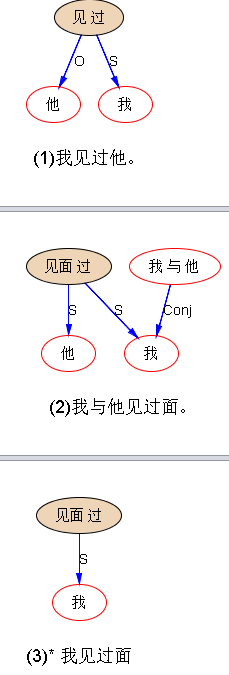

However, things are not always this simple. Compare the following Chinese sentences of the same form NP NP V:

2a) dianxin wo chi le.

Dim-Sum I eat LE.

The Dim Sum I have eaten.

Note: LE is a particle for perfect aspect.

2b) wo dianxin chi le.

I have eaten the Dim Sum.

Who eats what? There is no formal way but to resort to the semantic constraint imposed by the notion eat to reach the correct interpretation [Li, W. & McFetridge 1995].

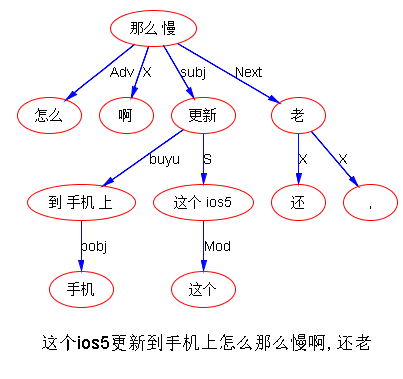

Of course, if we want to maintain the purity of syntax, it could be argued that syntax will only render possible interpretations and not the interpretation. It is up to other components (semantic filter and/or other filters) of grammar to decide which interpretation holds in a certain context or discourse. The power of syntax lies in the ability to identify structural ambiguities and to render possible corresponding interpretations. We call this type of linguistic design a syntax-before-semantics model. While this is one way to organize a grammar, we found it unsatisfactory for two reasons. First, it does not seem to simulate the linguistic process of human comprehension closely. For human listeners, there are no ambiguities involved in sentences 2a) and 2b). Secondly, there is considerable cost on processing efficiency in terms of computer implementation. This efficiency problem can be very serious in the analysis of languages like Chinese with virtually no inflection.

Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG) [Pollard & Sag 1994, 1987] assumes a lexicalist approach to linguistic analysis and advocates an integrated model of syntax and the other components of grammar. It serves as a desirable framework for the integration of the semantic constraint in establishing syntactic structures and interpretations. Therefore, we proposed to enforce the semantic constraint that animate being eats food directly in the lexical entry chi (eat) [Li, W. & McFetridge 1995]: chi (eat) requires an animate NP subject and a food NP object. It correctly addresses who-eats-what problem for sentences like 2a) and 2b). In fact, this type of semantic constraint (selection restriction) has been widely used for disambiguation in NLP systems.

The problem is, the constraint should not always be enforced. In the practice of communication, deviation from the constraint is common and deviation is often deliberately applied to help render rhetorical expressions.

3) xiang chi yueliang, ni gou de3 zhao me?

want eat moon, you reach DE3 -able ME?

Wanting to eat the moon, but can you reach it?

Note: DE3 is a particle, introducing a postverbal adjunct of result or capability. ME is a sentence final particle for yes-no question.

4) dajia dou chi shehui zhuyi, neng bu qiong me?

people all eat social -ism, can not poor ME

Everyone is eating socialism, can it not be poor?

yueliang (moon) is not food, of course. It is still some physical object, though. But in 4), shehui zhuyi (socialism) is a purely abstract notion. If a parser enforces the rigid semantic constraint, there are many such sentences that will be rejected without getting a chance to be interpreted. The fact is, we do have interpretations for 3) and 4). Hence an adequate grammar should be able to accommodate those interpretations.

To capture such deviation, Wilks came up with his Preference Semantics [Wilks 1975, 1978]. A sophisticated mechanism is designed to calculate the semantic weight for each possible interpretation, i.e. how much it deviates from the preference semantic constraint. The final choice will be given to the interpretation with the most semantic weight in total. His preference model simulates the process of how human comprehends language more closely than most previous approaches.

The problem with this design is the serious computational complexities involved in the model [Huang 1987]. In order to calculate the semantic weight, the preference semantic constraint is loosened step by step. Each possible substructure has to be re-tried with each step of loosening. It may well lead to combinatorial explosion.

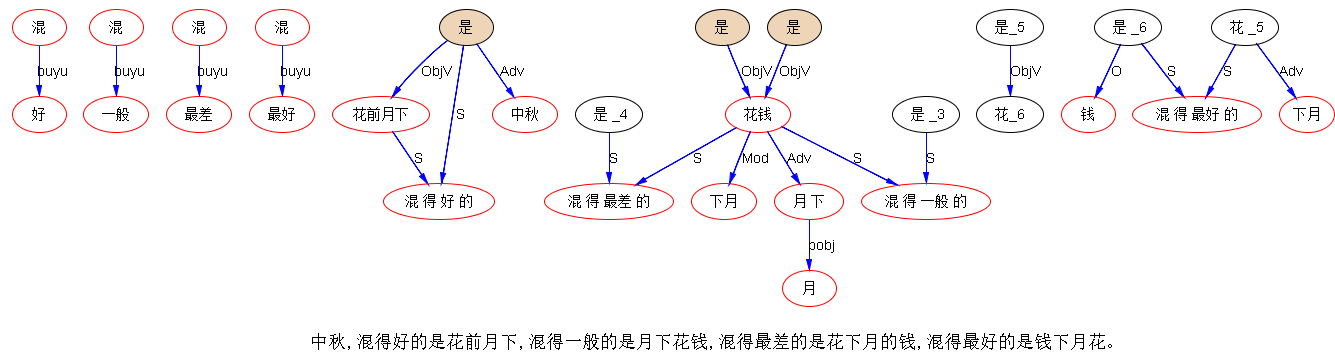

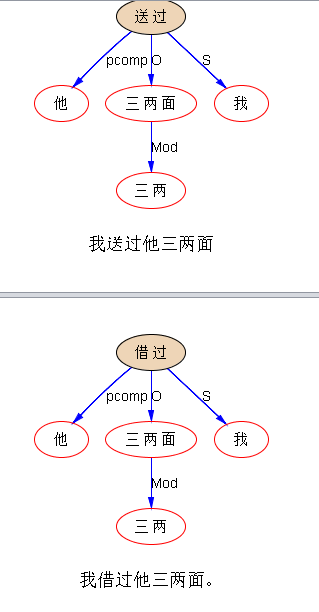

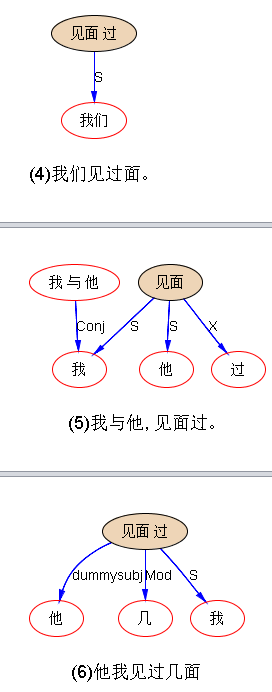

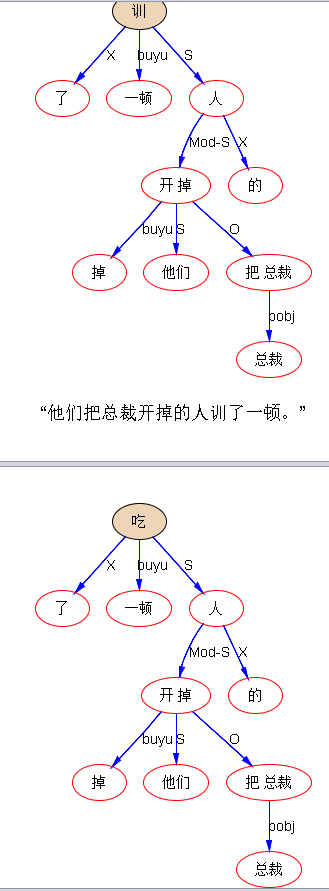

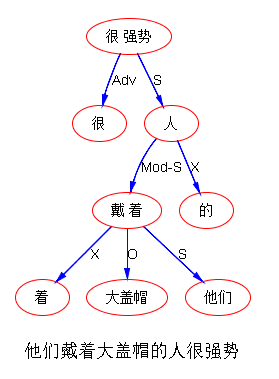

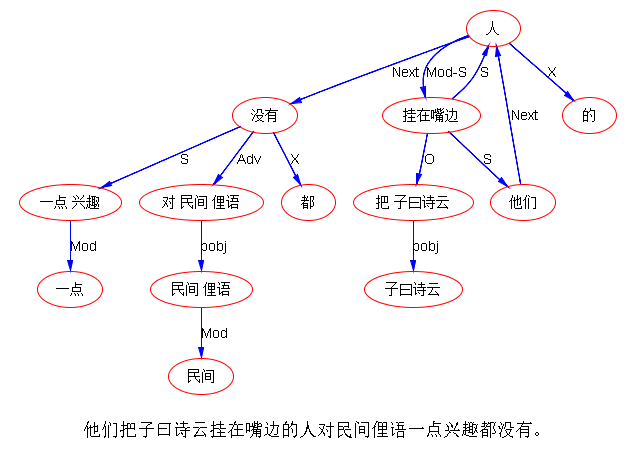

What we are proposing here is to look at semantic deviation in the light of the interaction of the syntactic constraint and the semantic constraint. In concrete terms, the loosening of the semantic constraint is conditioned by syntactic patterns. Syntactic pattern is defined as the representation of an argument structure in surface form. A pattern consists of 2 parts: a structure's syntactic constraint (in terms of the syntactic categories and configuration, word order, function words and/or inflections) and its interpretation (role assignment). For example, for Chinese transitive structure, NP V NP: SVO is one pattern, NP NP V: SOV is another pattern, and NP [ba NP] V: SOV (the BA construction) is still another. The expressive power of a language is indicated by the variety of patterns used in that language. Our design will account for some semantic deviation or rhetorical phenomena seen in everyday Chinese without the overhead of computational complexities. We will focus on Chinese transitive verb patterns for illustration of this approach.

- Chinese transitive patterns

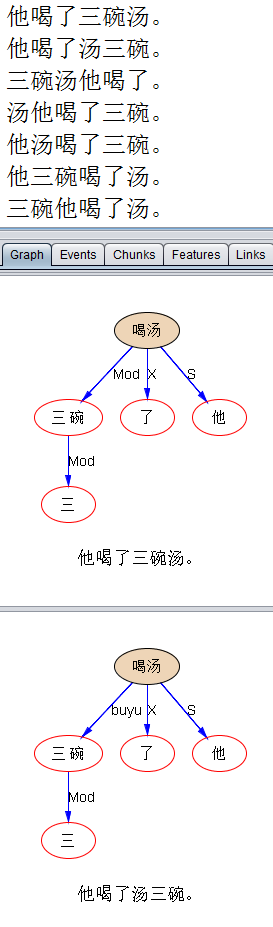

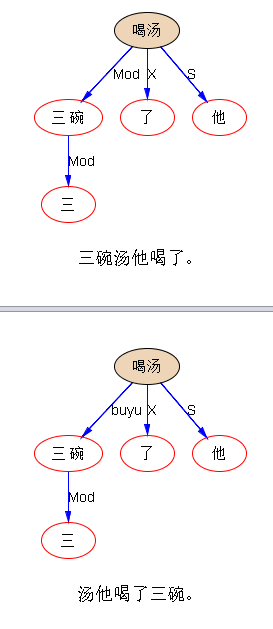

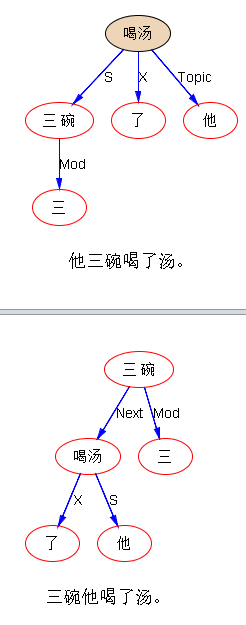

Assuming three notional signs wo (I), chi (eat) and dianxin (Dim Sum), there are maximally 6 possible combinations in surface word order, out of which 3 are grammatical in Chinese.[1]

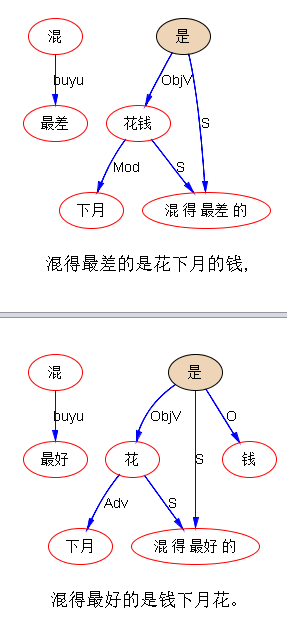

5a) wo chi le dianxin. SVO

5b) wo dianxin chi le. SOV

5c) dianxin wo chi le. OSV

SVO is the canonical word order for Chinese transitive structure. When a string of signs matches the order NP V NP, the semantic constraint has to yield to syntax for interpretation.

NP V NP: SVO

6) daodi shi ni zai du shu ne,

haishi shu zai du ni ne?

on-earth be you ZAI read book NE,

or book ZAI read you NE?

Are you reading the book, or is the book reading you, anyway?

Note: ZAI is a particle for continuous aspect.

NE is a sentence final particle for or-question.

Same as in the English equivalent, the interpretation of 6) can only be SVO, no matter how contradictory it might be to our common sense. In other words, in the form of NP V NP, syntax plays a decisive role.

In contrast, to interpret the form NP NP V as SOV in 2b), the semantic constraint is critical. Without the enforcement of the semantic constraint, the interpretation of SOV does not hold. In fact, this SOV pattern (NP1 NP2 V: SOV) has been regarded as ungrammatical in a Case Theory account for Chinese transitive structure in the framework of GB. According to their analysis, something similar to this pattern constitutes the D‑Structure for transitive pattern and Chinese is an underlying SOV language (called "SOV Hypothesis": see the survey in Gao 1993). In the surface structure, NP2 is without case on the assumption that V assigns its CASE only to the right. One has to either insert the case-marker ba to assign CASE to it (the BA construction) or move it to the right of V to get its CASE (the SVO pattern). This analysis suffers from not being able to account for the grammaticality of sentences like 2b). However, by distinguishing the deep pattern SOV from the 2 surface patterns (the SVO and the BA construction), the theory has its merit to alert us that the SOV pattern seems to be syntactically problematic (crippled, so to speak). This is an insightful point, but it goes one step too far in totally rejecting the SOV pattern in surface structure. If we modify this idea, we can claim that SOV is a syntactically unstable pattern and that SOV tends to (not must) "transform" to the SVO or the BA construction unless it is reinforced by semantic coherence (i.e. the enforcement of the semantic constraint). This argument in the light of syntax-semantics interaction is better supported by the Chinese data. In essence, our account is close to this reformulated argument, but in our theory, we do not assume a deep structure and transformation. All patterns are surface constructions. If no sentences can match a construction, it is not considered as a pattern by our definition.

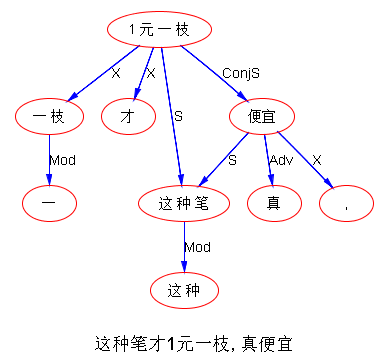

This type of unstable pattern which depends on the semantic constraint is not limited to the transitive phenomena. For example, the type of Chinese NP predicate defined in [Li, W. & McFetridge 1995] is also a semantics dependent pattern. Compare:

7a) zhe zhang zhuozi san tiao tui.

this Cl. table(furniture) three Cl. leg

This table is three-legged.

Note: Cl for classifier.

7b) * zhe zhang ditu san tiao tui.

this Cl. map(non-furniture) three Cl. leg

There is clearly a semantic constraint of the NP predicate on its subject: it should be furniture (or animate). Without this "semantic agreement", Chinese NP is normally not capable of functioning as a predicate, as shown in 7b).

Between semantics dependent and semantics independent patterns, we may have partially dependent patterns. For example, in NP NP V: OSV, it seems that the semantic constraint on the initial object is less important than the semantic constraint on the subject.

8) shitou wo ye xiang chi, kexi yao bu dong.

stone(non-food) I(animate) also want eat, pity chew not -able

Even stones I also want to eat, but it's such a pity that I am not able to chew them.

If the constraint on the object matches well, is the subject allowed to be semantically deviant?

9) ? dianxin zhuozi chi le.

Dim-Sum(food) table(non-animate) eat LE.

Those are the marginal cases, a grammar may choose to be more tolerable to accept it or to be more restrained to reject it.

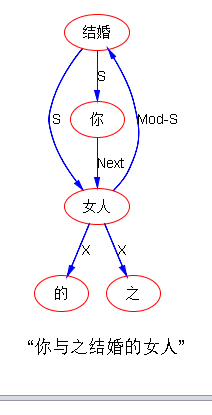

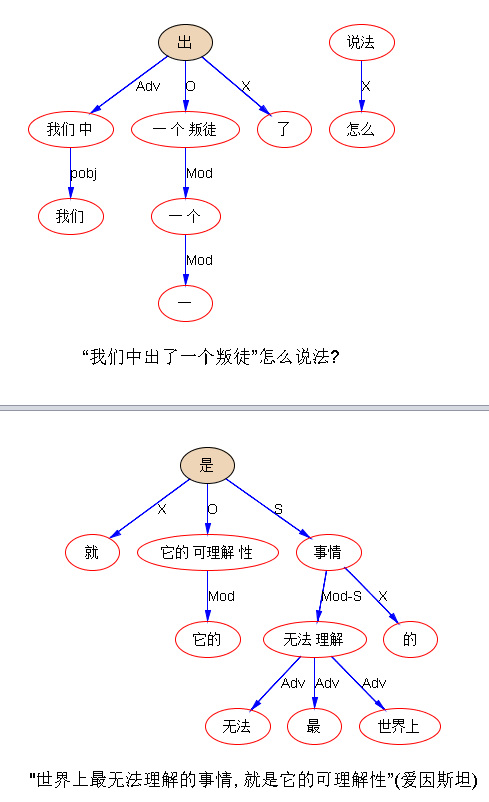

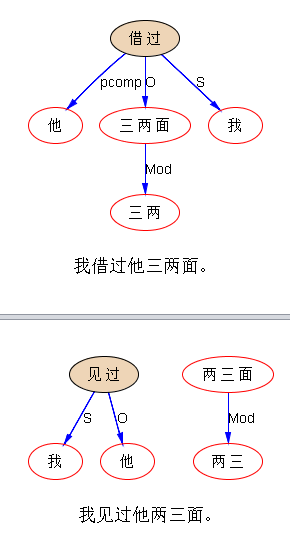

Unlike SOV, but similar to its English counterpart, OSV is one type of Chinese topic constructions and the relationship between the initial O and V is of long distance dependency.

10a) dianxin wo xiangxin ni yiwei Lisi chi le.

Dim-Sum I believe you think Lisi eat LE

The Dim Sum I believe you think that Lisi ate.

10b) * Lisi wo xiangxin ni yiwei dianxin chi le.

10b) will not be accepted in our model because (1) it cannot be interpreted as OSV since it violates the semantic constraint on S: dianxin is not animate; (2) it can neither be interpreted as SOV since it violates the configurational constraint: SOV is simply not of a long distance pattern. In fact, NP NP V: SOV is such a restricted pattern in Chinese that it not only excludes any long distance dependency but even disallows some adjuncts. Compare 11a) in the OSV pattern and 11b) and 11c) in the SOV pattern:

11a) dianxin wo jinjinyouwei de2 chi le.

Dim-Sum I with-relish DE2 eat LE

The Dim Sum I ate with relish.

Note: DE2 is a particle introducing a preverbal adjunct of manner.

11b) * wo dianxin jinjinyouwei de2 chi le.

11c) * wo jinjinyouwei de2 dianxin chi le.

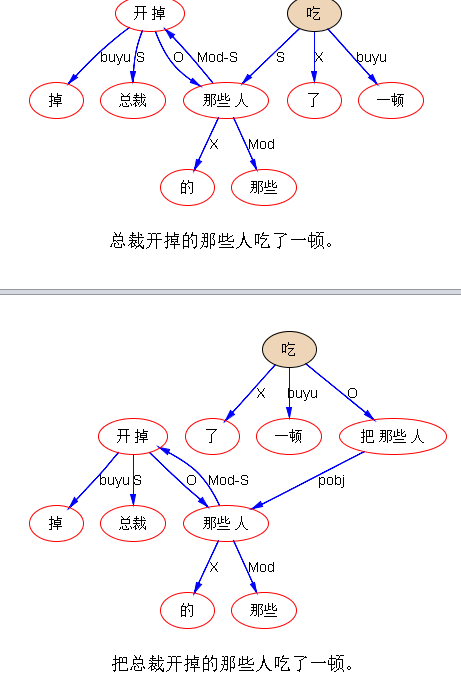

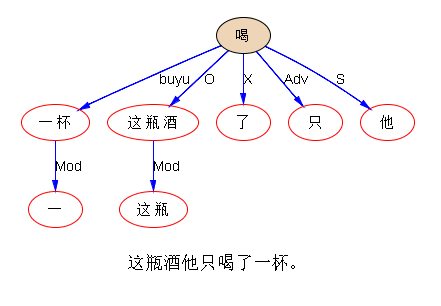

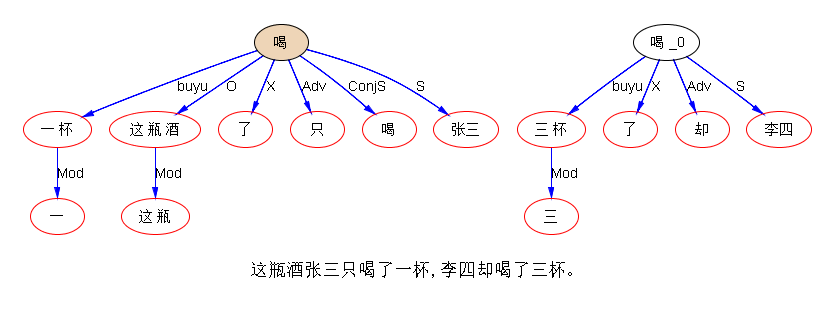

There is another pattern of the linear order SOV, the Chinese notorious BA construction. ba is usually regarded as a preposition which introduces a preverbal object for transitive verbs.

NP [ba NP] V: SOV

12a) wo ba dianxin jinjinyouwei de2 chi le.

I BA Dim-Sum with-relish DE2 eat LE

I ate the Dim Sum with relish.

12b) wo jinjinyouwei de2 ba dianxin chi le.

With relish, I ate the Dim Sum.

12c) dianxin ba wo jinjinyouwei de2 chi le.

The Dim Sum ate me with relish.

12d) dianxin jinjinyouwei de2 ba wo chi le.

With relish, the Dim Sum ate me.

For the OSV order, there is another so-called BEI construction. The BEI construction is usually regarded as an explicit passive pattern in Chinese.

NP [bei NP] V: OSV

13a) dianxin bei wo chi le.

Dim-Sum BEI I eat LE

The Dim Sum was eaten by me.

13b) wo bei dianxin chi le.

I was eaten by the Dim Sum.

The BEI construction and the BA construction are both semantics independent. In fact, any pattern resorting to the means of function words in Chinese seems to be sufficiently independent of the semantic constraint.

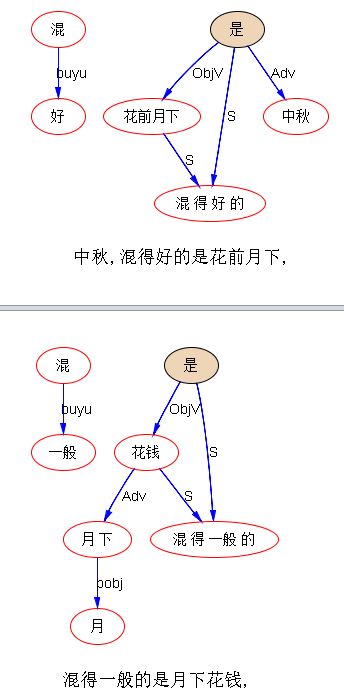

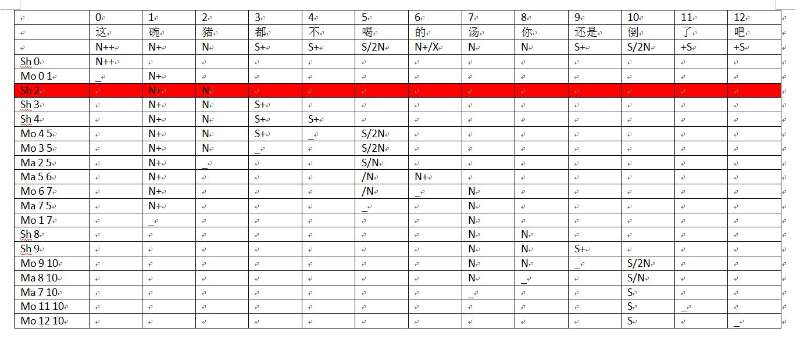

To conclude, semantic deviation often occurs in some more independent patterns, as seen in 5d2), 6), 8), 12c), 12d), 13b). Close study reveals that different patterns result in different reliance on the semantic constraint, as summarized in the following table.

syntactic pattern semantic dependence

NP V NP: SVO no dependence

NP [ba NP] V: SOV no dependence

NP [bei NP] V: OSV no dependence

NP NP V: OSV partial dependence

NP NP V: SOV full dependence

............

It should be emphasized that this observation constitutes the rationale behind our approach.

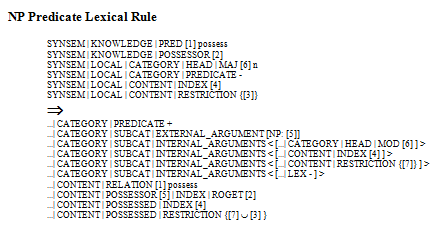

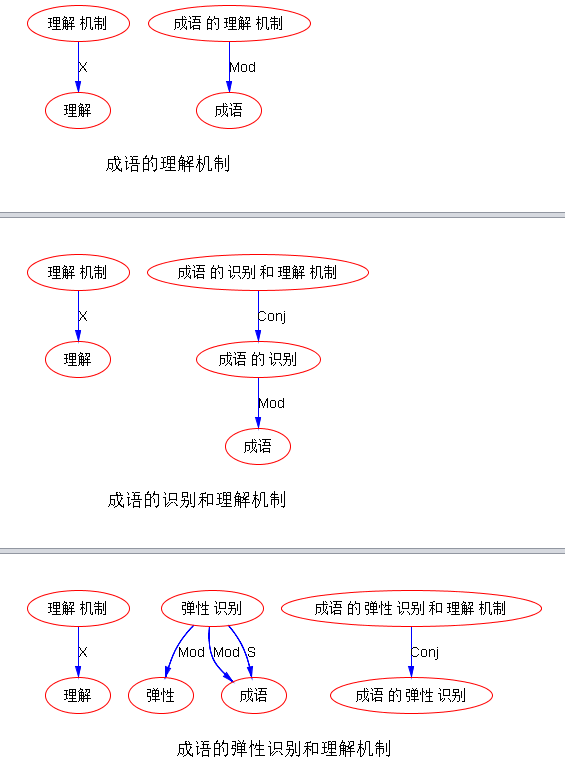

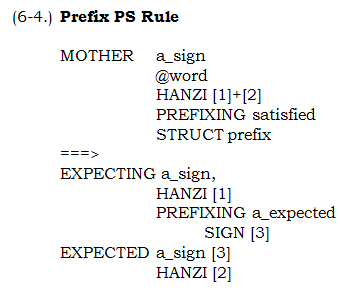

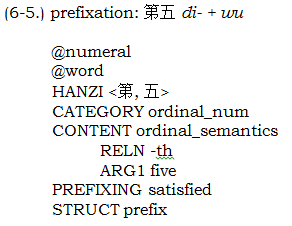

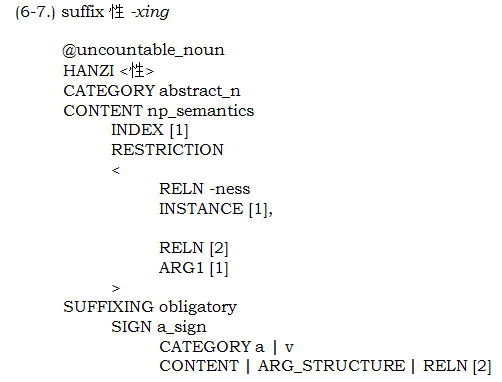

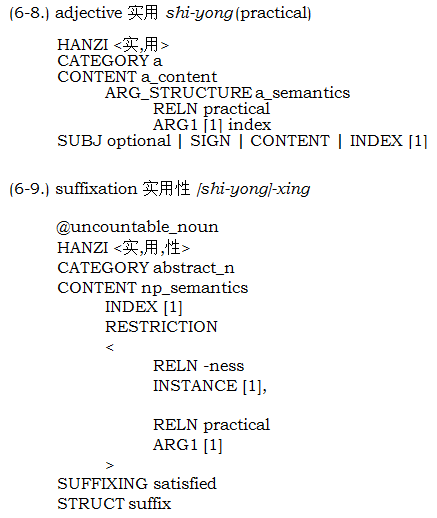

- Formulation of lexical rules

Based on the above observation, we have designed a syntax-semantics combined model. In this model, we take a lexical rule approach to Chinese patterns and the related problem of semantic deviation.

A lexical rule takes as its input a lexical entry which satisfies its condition and generates another entry. Lexical rules are usually used to cover lexical redundancy between related patterns. The design of lexical rules is preferred by many grammarians over the more conventional use of syntactic transformation, especially for lexicalist theories.

Our general design is as follows, still using chi (eat) for illustration:

(1) Syntactically, chi (eat) as a transitive verb subcategorizes for a left NP as its subject and a right NP as its object.

(2) Semantically, the corresponding notion eat expects an entity of category animate as its logical subject and an entity of category food as its logical object. Therefore the common sense (knowledge) that animate being eats food is represented.

(3) The interaction of syntax and semantics is implemented by lexical rules. The lexical rules embody the linguistic generalizations about the transitive patterns. They will decide to enforce or waive the semantic constraint based on different patterns.

As seen, syntax only stipulates the requirement of two NPs as complements for chi and does not care about the NPs' semantic constraint. Semantics sets its own expectation of animate entity and food entity as arguments for eat and does not care what syntactic forms these entities assume on the surface. It is up to lexical rules to coordinate the two. In our model, the information in (1) and (2) is encoded in the corresponding lexical entry and the lexical rules in (3) will then be applied to expand the lexicon before parsing begins. Driven by the expanded lexicon, analysis is implemented by a lexicalist parser to build the interpretation structure for the input sentence. Following this design, there will be sufficient interaction between syntax and semantics as desired while syntax still remains to be a self-contained component from semantics in the lexicon. More importantly, this design does not add any computational complexities to parsing because in order to handle different patterns, the similar lexical rules are also required even for a pure syntax model.

Before we proceed to formulate lexical rules for transitive patterns, we should make sure what a transitive pattern is. As we defined before, a pattern consists of 2 parts: a structure's syntactic constraint and the corresponding interpretation. Word order is important constraint for Chinese syntax. In addition to word order, we have categories and function words (preposition, particle, etc.). As for interpretation, transitive structure involves 3 elements: V (predicate) and its arguments S (logical subject) and O (logical object). There is a further factor to take into account: Chinese complements are often optional. In many cases, subject and/or object can be omitted either because they can be recovered in the discourse or they are unknown. We call those patterns elliptical patterns (with some complement(s) omitted), in contrast to full patterns. With these in mind, we can define 10 patterns for Chinese transitive structure: 5 full patterns and 5 elliptical patterns.

We now investigate these transitive patterns one by one and try to informally formulate the corresponding lexical rules to capture them. Please note that the basic input condition is the same with all the lexical rules. This is because they share one same argument structure - transitive structure.

Lexical rule 1:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> NP1 V NP2: SVO

The above notation for the lexical rule should be quite obvious. The input of the rule is a transitive verb which subcategorizes for two NPs: NP1 and NP2 and whose corresponding notion expects two arguments of constr1 and constr2. NP is syntactic category, and constr is semantic category (human, animate, food, etc.). The output pattern is in a defined word order SVO and waives the semantic constraint.

Lexical rule 2:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> [NP1, constr1] [NP2, constr2] V: SOV

Please note that the semantic constraint is enforced for this SOV pattern. Since this pattern shares the form NP NP V with the OSV pattern, it would be interesting to see what happens if a transitive verb has the same semantic constraint on both its subject and object. For example, qingjiao (consult) expects a human subject and a human object.

14) ta ni qingjiao guo me?

he(human) you(human) consult GUO ME

Him, have you ever consulted?

Note: GUO is a particle for experience aspect.

15) ni ta qingjiao guo me?

You, has he ever consulted?

In both cases, the interpretation is OSV instead of SOV. Therefore, we need to reformulate Lexical rule 2 to exclude the case when the subject constraint is the same as the object constraint.

Lexical rule 2' (refined version):

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2), (constr1 not = constr2))

--> [NP1, constr1] [NP2, constr2] V: SOV

Lexical rule 3:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> NP1 [ba NP2] V: SOV

This is the typical BA construction. But not every transitive verb can assume the BA pattern. In fact, ba is one of a set of prepositions to introduce the logical object. There are other more idiosyncratic prepositions (xiang, dao, dui, etc.) required by different verbs to do the same job.

16a) ni qingjiao guo ta me?

you consult GUO he ME

Have you ever consulted him?

16b) ni xiang ta qingjiao guo me?

you XIANG he consult GUO ME

Have you ever consulted him?

16c) * ni ba ta qingjiao guo me?

you BA he consult GUO ME

17a) ta qu guo Beijing.

he go-to GUO Beijing

He has been to Beijing.

17b) ta dao Beijing qu guo.

he DAO Beijing go-to GUO

He has been to Beijing.

17c) * ta ba Beijing qu guo.

he BA Beijing go-to GUO

18a) ta hen titie zhangfu.

she very tenderly-care-for husband

She cares for her husband very tenderly.

18b) ta dui zhangfu hen titie.

she DUI husband very tenderly-care-for

She cares for her husband very tenderly.

18c) * ta ba zhangfu hen titie.

she BA husband very tenderly-care-for

This originates from different theta-roles assumed by different verb notions on their object argument: patient, theme, destination, to name only a few. These theta-roles are further classification of the more general semantic role logical object. We can rely on the subcategorization property of the verb for the choice of the preposition literal (so-called valency preposition). With the valency information in place, we now reformulate Lexical rule 3 to make it more general:

Lexical rule 3' (refined version):

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2), (valency_preposition=P), (P not = null))

--> NP1 [P NP2] V: SOV

Lexical rule 4:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> NP2 ... [NP1, constr1] V: OSV

This is a topic pattern of long distance dependency. It is up to different formalisms to provide different approaches to long-distance phenomena. In our present implementation, NP2 is placed in a feature called BIND to indicate the nature of long distance dependency. One phrase structure rule Topic Rule is designed to use this information and handle the unification of the long distance complement properly.

Following the topic pattern, the passive BEI construction is formulated in Lexical rule 5.

Lexical rule 5:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> NP2 [bei NP1] V: OSV

We now turn to elliptical patterns.

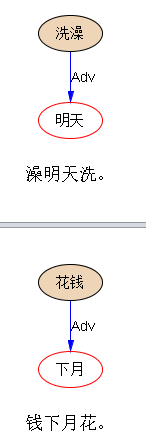

Lexical rule 6:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> V NP2: VO

19) chi guo jiaozi me?

eat GUO dumpling ME

Have (you) ever eaten dumpling?

Lexical rule 7:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> [NP1, constr1] V: SV

20) wo chi le.

I eat LE

I have eaten (it).

21) ji chi le.

chicken1(animate) eat LE

The chicken has eaten (it).

Like its English counterpart, ji (chicken) has two senses: (1) chicken1 as animate; (2) chicken2 as food. We code this difference in two lexical entries. Only the first entry matches the semantic constraint on the subject in the pattern and reaches the above SV interpretation in 21). Interestingly enough, the same sentence will get another parse with a different interpretation OV in 23) because the second entry also satisfies the semantic constraint on the object in the OV pattern in Lexical rule 8.

22) ni qingjiao guo me?

you consult GUO ME

Have you consulted (someone)?

22) indicates that the SV interpretation is preferred over the OV interpretation when the semantic constraint on the subject and the semantic constraint on the object happen to be the same. Hence the added condition in Lexical rule 8.

Lexical rule 8:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2), (constr1 not = constr2))

--> [NP2, constr2] V: OV

23) ji chi le.

chicken2(food) eat LE

The chicken has been eaten.

Lexical rule 9:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> NP2 [bei V]: OV

24) dianxin bei chi le.

Dim-Sum BEI eat LE

The Dim Sum has been eaten.

Lexical rule 10:

V ((NP1, NP2), (constr1, constr2)) --> V: V

25) chi le me?

eat LE ME?

(Have you) eaten (it)?

- Implementation

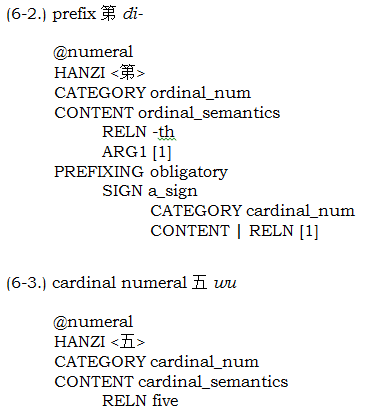

We begin with a discussion of some major feature structures in HPSG related to handling the transitive patterns. Then, we will show how our proposal works and discuss some related implementation issues.

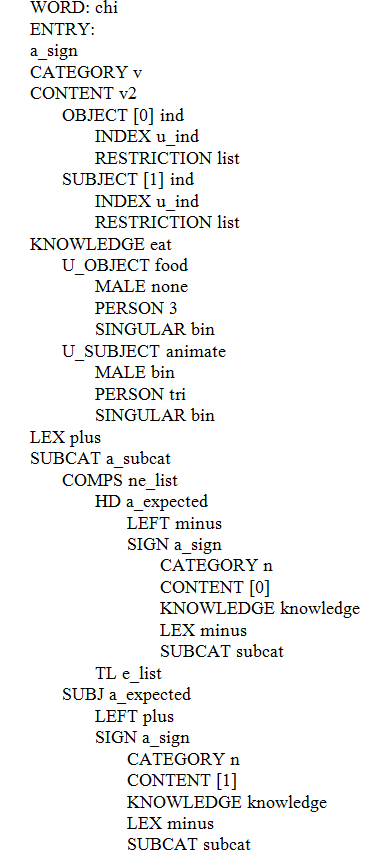

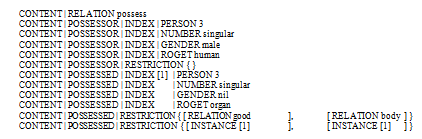

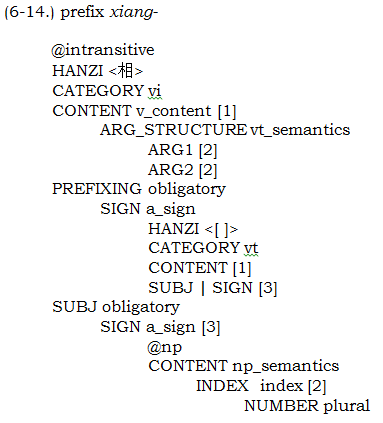

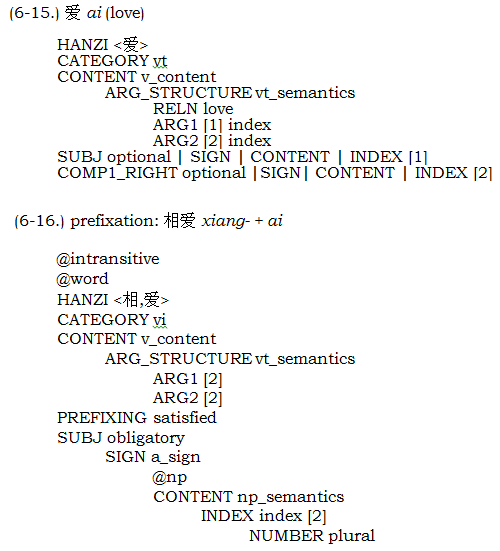

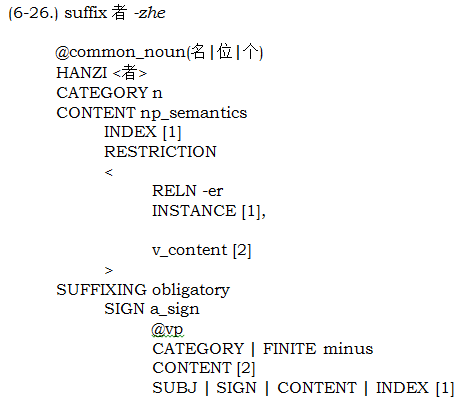

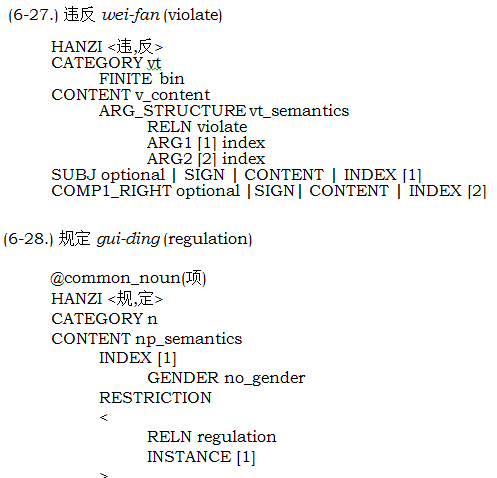

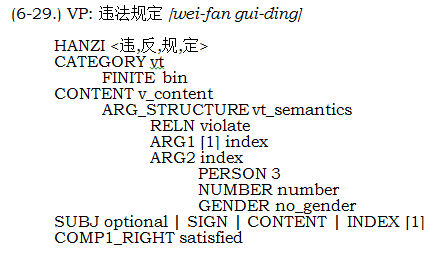

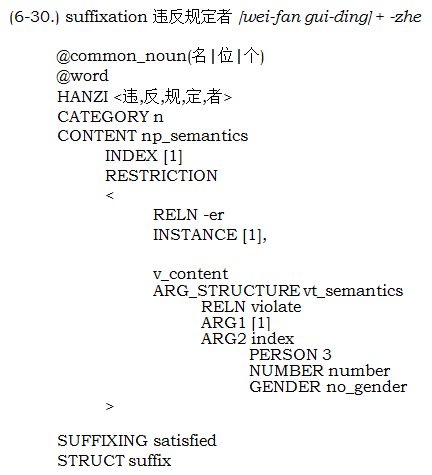

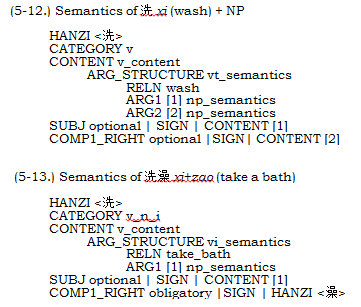

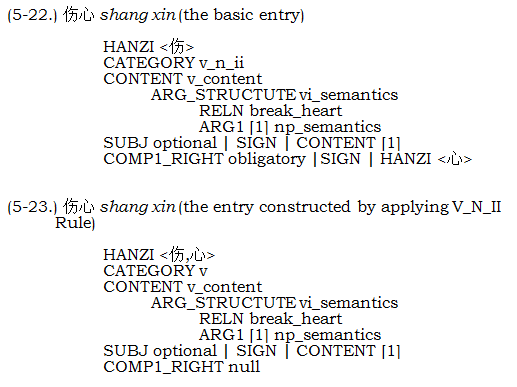

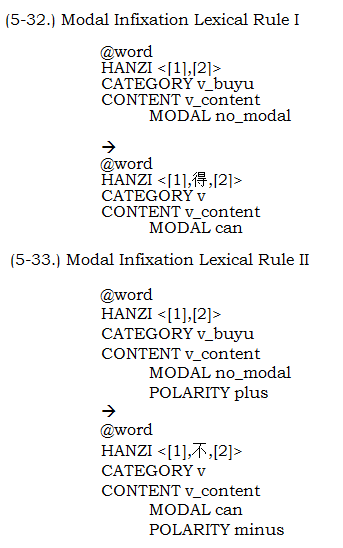

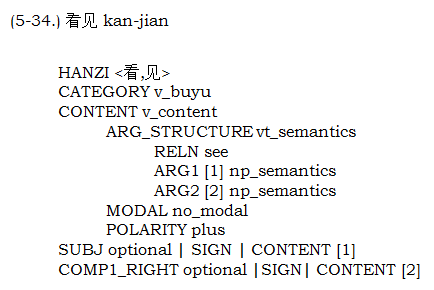

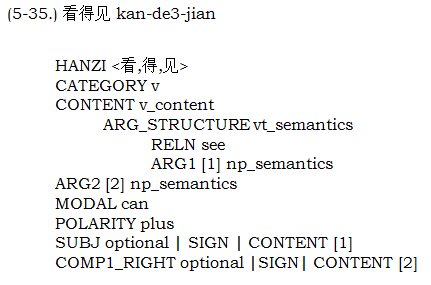

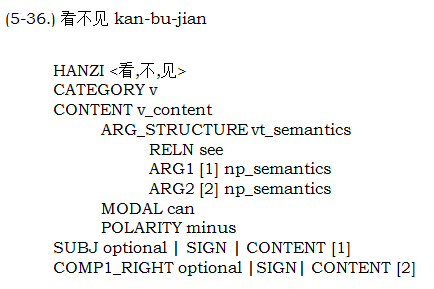

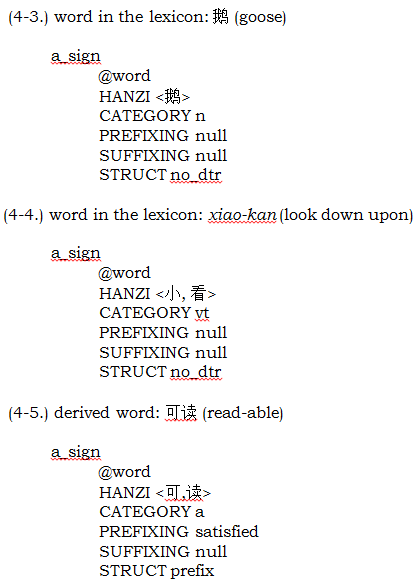

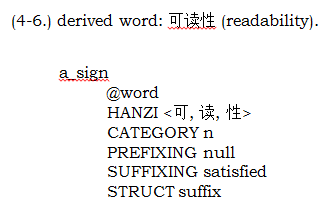

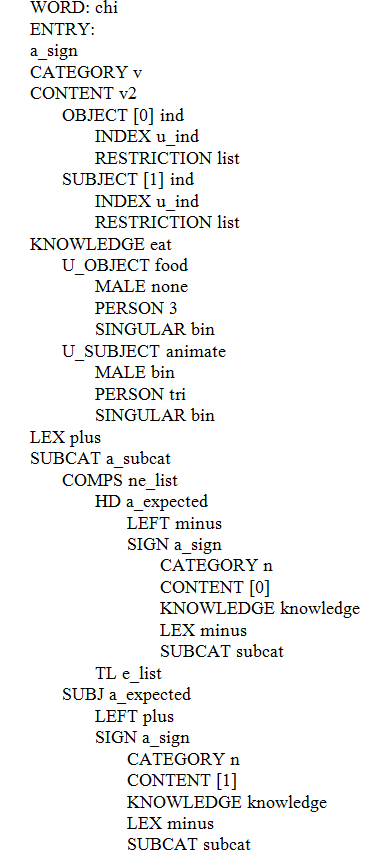

HPSG is a highly lexicalist theory. Most information is housed in the lexicon. The general grammar is kept to minimum: only a few phrase structure rules (called ID Schemata) associated with a couple of principles. The data structure is typed feature structure. The necessary part for a typed feature structure is the type information. A simple feature structure contains only the type information, but a complex feature structure can introduce a set of feature/value pairs in addition to the type information. In a feature/value pair, the value is itself a feature structure (simple or complex). The following is a sample implementation of the lexical entry chi for our Chinese HPSG grammar using the ALE formalism [Carpenter & Penn 1994].

Note: (1) Uppercase notation for feature; (2) Lowercase notation for type; (3) Number indices in square brackets for unification.

Leaving the notational details aside, what this roughly says is: (1) for the semantic constraint, the arguments of the notion eat are an animate entity and a food entity; (2) for the syntactic constraint, the complements of the verb chi are 2 NPs: one on the left and the other on the right; (3) the interpretation of the structure is a transitive predicate with a subject and an object. The three corresponding features are: (1) KNOWLEDGE; (2) SUBCAT; (3) CONTENT. KNOWLEDGE stores some of our common sense by capturing the internal relation between concepts. Such common sense knowledge is represented in linguistic ways, i.e. it is represented as a semantic expectation feature, which parallels to the syntactic expectation feature SUBCAT. KNOWLEDGE defines the semantic constraint on the expected arguments no matter what syntactic forms the arguments will take. In contrast, SUBCAT only defines the syntactic constraint on the expected complements. The syntactic constraint includes word order (LEFT feature), syntactic category (CATEGORY feature) and configurational information (LEX feature). Finally, CONTENT feature assigns the roles SUBJECT and OBJECT for the represented structure.

A more important issue is the interaction of the three feature structures. Among the three features, only KNOWLEDGE is our add-on. The relationship between SUBCAT and CONTENT has been established in all HPSG versions: SUBCAT resorts to CONTENT for interpretation. This interaction corresponds to our definition of pattern. Everything goes fine as far as the syntactic constraint alone can decide interpretation. When the semantic constraint (in KNOWLEDGE) has to be involved in the interpretation process, we need a way to access this information. In unification based theories, information flow is realized by unification (i.e. structure sharing, which is represented by the co-index of feature values). In general, we have two ways to ensure structure sharing in the lexicon. It is either directly co-indexed in the lexical entries, or it resorts to lexical rules. The former is unconditional, and the latter is conditional. As argued before, we cannot directly enforce the semantic constraint for every transitive pattern in Chinese, for otherwise our grammar will not allow for any semantic deviation. We are left with lexical rules which we have informally formulated in Section 3 and implemented in the ALE formalism.

CATEGORY is another major feature for a sign. The CATEGORY feature in our implementation includes functional category which can specify functional literal (function word) as its value. Function words belong to closed categories. Therefore, they can be classified by enumeration of literals. Like word order, function words are important form for Chinese syntactic constraint. Grammars for other languages also resort to some functional literals for constraint. In most HPSG grammars for English, for example, a preposition literal is specified in a feature called P_FORM. There are two problems involved there. First, at representation level, there is redundancy: P_FORM:x --> CATEGORY:p (where x is not null). In other words, there exists feature dependency between P_FORM and CATEGORY which is not captured in the formalism. Second, if P_FORM is designed to stipulate a preposition literal, we will ultimately need to add features like CL_FORM for classifier specification, CO_FORM for conjunction specification, etc. In fact, for each functional category, literal specification may be required for constraint in a non-toy grammar. That will make the feature system of the grammar too cumbersome. These problems are solved in our grammar implementation in ALE. One significant mechanism in ALE is its type inheritance and appropriateness specifications for feature structures [Carpenter & Penn 1994]. (Similar design is found in the new software paradigm of Object Oriented Programming.) Thanks to ALE, we can now use literals (ba, xiang, dao, dui, etc) as well as major categories (n, v, a, p, etc.) to define the CATEGORY feature. In fact, any intermediate level of subclassification between these two extremes, major categories and literals, can all be represented in CATEGORY just as handily. They together constitute a type hierarchy of CATEGORY. The same mechanism can also be applied to semantic categories (human, animate, food, etc.) to capture the thesaurus inference like human --> animate. This makes our knowledge representation much more powerful than in those formalisms without this mechanism. We will address this issue in depth in another paper Typology for syntactic category and semantic category in Chinese grammar.

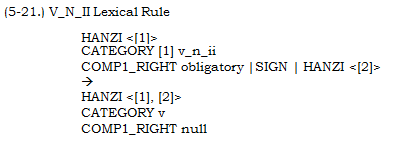

In the following, we give a brief description on how our grammar works. The grammar consists of several phrase structure rules and a lexicon with lexical entries and lexical rules. First, ALE compiles the grammar into a Prolog parser. During this process (at compile time), lexical rules are applied to lexical entries. In the case of transitive patterns, this means that one entry of chi will evolve into 10 entries. Please note that it is this expanded lexicon that is used for parsing (at run time).

At the level of implementation, we do not need to presuppose an abstract transitive structure as input of the lexical rules and from there generates 10 new entries for each transitive verb. What is needed is one pattern as the basic pattern for transitive structure and derives the other patterns. In fact, we only need 4 lexical rules to derive the other 4 full patterns from 1 basic full pattern. Elliptical patterns can be handled more elegantly by other means than lexical rules.[2]

The basic pattern constitutes the common condition for lexical rules. Although in theory any one of the 5 full patterns can be seen as the basic pattern, the choice is not arbitrarily made. The pattern we chose is the valency preposition pattern (the BA-type construction) NP1 [P NP2] V: SOV (see Lexical rule 3').[3] This is justified as follows. The valency preposition P (ba, xiang, dao, dui, etc.) is idiosyncratically associated with the individual verb. To derive a more general pattern from a specific pattern is easier than the other way round, for example, NP1 [P NP2] V: SOV --> NP1 V NP2: SVO is easier than NP1 V NP2: SVO --> NP1 [P NP2] V: SOV. This is because we can then directly code the valency preposition under CATEGORY in the SUBCAT feature and do not have to design a specific feature to store this valency information.

- Summery

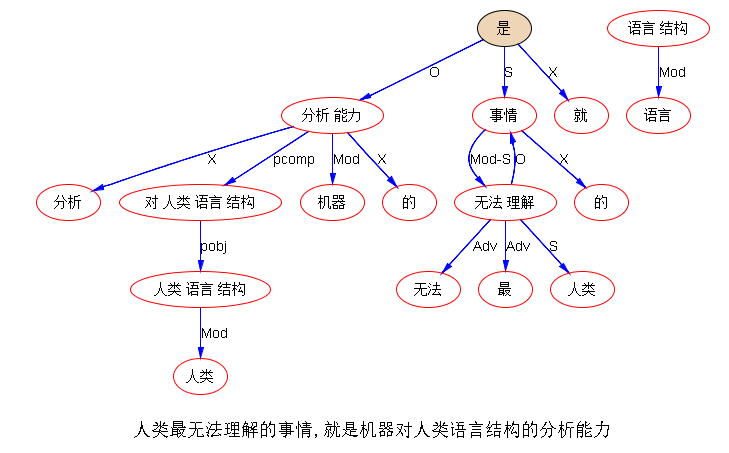

The ultimate aim for natural language analysis is to reach interpretation, i.e. to assign roles to the constituents. An old question is how syntax (form) and semantics (meaning) interact in this interpretation process. More specifically, which is a more important factor in Chinese analysis, the syntactic constraint or the semantic constraint? For the linguistic data we have investigated, it seems that sometimes syntax plays a decisive role and other times semantics has the final say. The essence is how to adequately handle the interface between syntax and semantics.

In our proposal, the syntactic constraint is seen as a more fundamental factor. It serves as the frame of reference for the semantic constraint. The involvement of the semantic constraint seems to be most naturally conditioned by syntactic patterns. In order to ensure their effective interaction, we accommodate syntax and semantics in one model. The model is designed to be based on syntax and resorts to semantic information only when necessary. In concrete terms, the system will selectively enforce or waive the semantic constraint, depending on syntactic patterns.

It needs to be advised that there are other factors involved in reaching a correct interpretation. For example, in order to recover the omitted complements in elliptical patterns, information from discourse and pragmatics may be vital. We leave this for future research.

References

Carpenter, B. & Penn, G. (1994): ALE, The Attribute Logic Engine, User's Guide, Version 2.0

Gao, Qian (1993): “Chinese BA-Construction: Its Syntax and Semantics”, OSU Working Papers in Linguistics 1993, Kathol A. & Pollard C. (eds.)

Huang, Xiuming (1987): “XTRA: The Design and Implementation of A Fully Automatic Machine Translation System”, Ph.D. dissertation.

Li, Audry (1990): Chapter 6 “Passive, BA, and topic constructions”, Order & Constituency in Mandarin Chinese. Kluwer Academic Publishers

Li, Wei & McFetridge, Paul (1995): “Handling Chinese NP predicate in HPSG”, Proceedings of PACLING-II, Brisbane, Australia

Pollard, Carl & Sag, Ivan A. (1994): Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Centre for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University, CA

Pollard, Carl & Sag, Ivan A. (1987): Information-based Syntax and Semantics. Vol. 1: Fundamentals. Centre for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University, CA

Wilks, Y.A. (1978): “Making Preferences More Active”, Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 11

Wilks, Y.A. (1975): “A Preferential Pattern-Seeking Semantics for Natural Language Interference”, Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 6

~~~~~~~~~~~~

* This research is part of my Ph.D. project on a Chinese HPSG-style grammar, supported by the Science Council of British Columbia, Canada under G.R.E.A.T. award (code: 61). I thank my supervisor Dr. Paul McFetridge for his supervision. He introduced me into the HPSG theory and provided me with his sample grammars. Without his help, I would not have been able to implement the Chinese grammar in a relatively short time. Thanks also go to Prof. Dong Zhen Dong and Dr. Ping Xue for their comments and encouragement.

[1] The other combinations are:

5d1) * dianxin chi le wo. OVS

5d2) dianxin chi le wo.

The Dim Sum ate me.

Note: It is OK with the 5d2) reading in the pattern NP V NP: SVO.

5e1) * chi le wo dianxin. VSO

5e2) chi le wo dianxin.

(Somebody) ate my Dim Sum.

Note: It is OK with the 5e2) reading of in the pattern V [NP1 NP2]: VO where NP1 modifies NP2.

5f1) * chi le dianxin wo. VOS

5f2) chi le dianxin, wo.

Eaten the Dim Sum, I have.

Note: It is OK in Spoken Chinese, with a short pause before wo, in a pattern like V NP, NP: VOS.

[2] The conventional configurational approach is based on the assumption that complements are obligatory and should be saturated. If saturation of complements were not taken as a precondition for a phrase, serious problems might arise in structural overgeneration. On the other hand, optionality of complement(s) is a real life fact. Elliptical patterns are seen in many languages and especially commonplace in Chinese. In order to ensure obligatoriness of complements, the lexical rule approach can be applied to elliptical patterns, as shown in Section 3. This approach maintains configurational constraint in tree building to block structural overgeneration, but the cost is great: each possible elliptical pattern for a head will have to be accommodated by a new lexical entry. With the type mechanism provided by ALE, we have developed a technique to allow for optionality of complement(s) and still maintain proper configurational constraint. We will address this issue in another paper Configurational constraint in Chinese grammar.

[3] This choice is coincidental to the base‑generated account of the BA construction in [Li, A. 1990], but that does not mean much. First, our so‑called basic pattern is not their D‑Structure. Second, our choice is based on more practical considerations. Their claim involves more theoretical arguments in the context of the generative grammar.

[Related]

Handling Chinese NP predicate in HPSG (old paper)

Notes for An HPSG-style Chinese Reversible Grammar

Outline of an HPSG-style Chinese reversible grammar

PhD Thesis: Morpho-syntactic Interface in CPSG (cover page)

PhD Thesis: Chapter I Introduction

PhD Thesis: Chapter II Role of Grammar

PhD Thesis: Chapter III Design of CPSG95

PhD Thesis: Chapter IV Defining the Chinese Word

PhD Thesis: Chapter V Chinese Separable Verbs

PhD Thesis: Chapter VI Morpho-syntactic Interface Involving Derivation

PhD Thesis: Chapter VII Concluding Remarks

Overview of Natural Language Processing

Dr. Wei Li’s English Blog on NLP

![[坏笑] [坏笑]](https://img.t.sinajs.cn/t4/appstyle/expression/ext/normal/50/pcmoren_huaixiao_org.png)

白:

白: